@tobararbulu # mm@tobararbuluhttps://modernmoney.wordpress.com/index/

No idea at all!

Please, #LearnMMT:

Aipamena

Elon MuskImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. @elonmusk

@elonmusk

abe. 18

Exactly right. ALL government spending is taxation.

The government either taxes you directly or, by increasing the money supply, taxes you through inflation.

oooooo

Stephanie Kelton@StephanieKelton

ALL FEDERAL SPENDING EMITS TAX CREDITS (i.e. US$) THAT FUND TAXPAYERS.

Aipamena

Tesla Owners Silicon Valley@teslaownersSV

2024 abe. 19

“ALL FEDERAL SPENDING IS TAXATION.” Elon Musk

Bideoa: https://x.com/i/status/1869843714102927823

Segida

Shifts in societal attitudes towards well-being mean that a degrowth strategy does not necessarily have to be political suicide https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62286

Bill Mitchell: Shifts in societal attitudes towards well-being mean that a degrowth strategy does not necessarily have to be political suicide

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62286)

January 9, 2025

At the end of World War 2, the Western nations were beset with paranoia about what the USSR might be planning. The West had essentially relied on the Soviet armed forces to defeat the Nazis through their efforts on the Eastern front, after Hitler had launched – Operation Barbarossa – which effectively ended the – Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact – signed in 1939 between Germany and the USSR. Following the War, the ‘spectre of Communism’ drove the Western political leaders to embrace social democracy and introduce policies that created the mass-consuming middle class in most countries, which was seen as a bulwark against the developemnt of a revolutionary working class movement and any further spread of Communism. While the interests of capital hated the welfare state and the rise of trade unions, they saw these developments as a means to protect their hegemony in the new world and the uncertainty that the – Cold War – engendered. Mass consumption was akin to Marx’s claims about religion being the ‘opium of the people’ and it has been a dominant part of life in advanced nations in the Post War period. It is one of the reasons that people think a degrowth strategy can never be embraced by the political class because it would confront a population besotted with material accumulation and consumption. However, research from Japan suggests that a strategy designed to reduce material consumption will not “reduce individual happiness and collective wellbeing” (Source) and a decoupling between growth and human happiness is indeed possible, which means the political class, if they are courageous enough, can introduce policies that promote degrowth.

I am also researching the link between growth and human happiness.

The article I cited in the Introduction – Is happiness possible in a degrowth society? – was published in the Futures journal in December 2022 (Volume 144) and was written by three researchers – Hikaru Komatsu (National Taiwan University), Jeremy Rappleye (Kyoto University), and Yukiko Uchida (Kyoto University).

The Japanese Cabinet Office has conducted an annual survey – 社会意識に関する世論調査 (Public opinion survey on social consciousness) – since 1948, which provides a very rich data source for researchers.

I have been working with this data for some time now, untangling the complexity of the information that spans such a long period of time within which the Japanese nation has evolved from a defeated, occupied country with widespread poverty into one of the rich, advanced nations of the world.

The survey interviews produce around 6,000 ‘valid sample’ each year from 10,000 interviewees, which is means it is a great source of data for researchers like myself.

Survey officers conduct these face-to-face interviews of Japanese nationals over 18 years of age in locations throughout Japan.

There are other surveys that supplement this data:

1. 日本人の意識」調査 (Survey of Japanese Attitudes) – which is conducted by NHK’s Broadcasting Cultural Research Institute.

2. 日本人の国民性調査とは (Japanese National Character Survey) – which is conducted b the – 統計数理研究所 (Institute of Statistical Mathematics) – Japan’s national research institute for statistical sciences located in Tokyo.

The results of these surveys allow questions pertaining to the link between material growth (GDP growth) and happiness to be interrogated, which helps determine whether their is any political chance that a degrowth strategy could succeed.

Most progressively-minded commentators, who accept that climate change is now threatening human existence, advocate a ‘green growth’ strategy, which entails reducing the fossil-fuel component of growth to help moderate the damage that extensive use of carbon-based resources are doing.

It is a sort of have it both ways strategy and is motivated by the belief that politically it is simply not possible to significantly reduce the material prosperity of populations in the advanced nations through political interventions.

The ‘green growthers’ consider the mass consumption ethos to be so ingrained that it would be political suicide for a political party to advocate retrenching that aspect of our behaviour.

They believe that happiness comes from material growth and so the only political option is to redirect from from ‘brown’ to ‘green’, while essentially maintaining material consumption levels.

I recall in my student days, people telling me that capitalism was a natural fit for humanity because we are all self-interested and greedy when push-comes-to-shove.

I wrote about that idea in this blog post – Humans are intrinsically anti neo-liberal (May 22, 2017).

The ‘green growth’ assumption that growth makes us happy is a replay of that claim.

I have also noted before that humanity is currently plundering nature 1.7 times faster than our planet’s ecosystems can regenerate

Please read my blog post – We are 1.7 times over regenerative capacity and the world’s population control must be reduced (August 21, 2024) – for more discussion on this point.

On average, nations reached – Earth Overshoot day – last year on August 1, 2024, which means that we should have all stopped producing and consuming then.

The situation varies greatly across different countries.

What this means is that the strategy to bring that resource demand back into the realms where regeneration is possible cannot include on-going growth, ‘green’ or otherwise.

That observation is the basis for moving our focus to a degrowth strategy, whatever that entails.

The question is whether it runs against our desire for happiness, which ‘green growthers’ assume is correlated (at least) with material aspirations.

Commentators point to surveys taken during recessions that show people are more likely to be depressed when they face job loss.

They use that cyclical response as a justification for their assertion that material growth is necessary for underlying happiness.

Of course, it is a poor example, because in a recession, the lower income cohorts suffer disproportionately, while the upper income group tend to prosper – adding wealth (for example, via forced sale of real estate by workers rendered unemployed).

A careful degrowth strategy would not impose these sorts of disproportionate costs on the poorest cohort.

There is a growing body of research that indicates that there is no necessary link between those aspirations and outcomes and our sense of well-being.

The article I cited above is one of several in that category and takes an interesting long-term view by tracing shifts in social attitudes in Japan over the last several decades which the mainstream commentariate initially referred to as the ‘lost decade’ (when the slowdown after the 1991 property market collapse was 10 years in).

The researchers found that:

When economic standards started declining, the level of subjective wellbeing did, in fact, decline during the first five years. However, the level of subjective wellbeing subsequently stopped declining and even started improving, despite no apparent recovery in economic standards.

To establish this finding, they used survey data I mentioned above.

A question in the survey that gave the researchers vital information: How satisfied are you with your current life? – “Respondents were required to choose one among the following five options: (1) satisfied, (2) somewhat satisfied, (3) can’t say either way, (4) somewhat dissatisfied, and (5) dissatisfied.”

From the answers, a “mean level of subjective wellbeing” was constructed.

The results were supplemented by similar answers in the NHK and the ISM surveys.

The interesting outcome of the research and of the survey evidence (the latter which is motivated my own work at present) was the shift over time in the way Japanese people evaluated their sense of well-being.

The early surveys were found to irrelevant in the modern era because of these shifts, which influenced the survey design as time passed.

The cited research noted that:

Japan previously emphasized individual achievement and status, the dominant form of wellbeing underpinning modernity. Yet, there has been a shift in understanding of happiness and wellbeing: away from individual achievements towards harmonious relationships. This shift in the concept of wellbeing might have occurred in accordance with the decline in economic standards. Individual achievements would require an abundance of resources, opportunities, and thus greater materialistic consumption, a difficult set of conditions to maintain in a society with declining economic standards.

That shift is demonstrated in a number of research papers and is very interesting because it suggests that societies adapt to changing circumstances and shift away from dominant ideologies more than we might think.

The following graph shows the responses to satisfied and dissatisfied questions from 1995 to 2019 with the lower panel breaking down the responses into age cohorts.

Clearly, in the aftermath of the bubble crash in the early 1990s and the sales tax hike in 1997, people expressed rising dissastification and declining satisfaction.

But after 2000, that pattern reversed.

And as the authors note: “The gradual recovery of wellbeing over the past two decades was greatest among younger age cohorts”.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Further, the responses that supported:

… individual achievement (“do what they want” and “think about themselves”) … decreased, while those who chose the options emphasizing harmonious relationships (i.e., “do something for others” and “help others”) increased over the same two decade span … these tendencies were more pronounced for younger age cohorts …

The conjecture is that the younger cohorts never experienced the rapid growth era in the 1960s and 1970s and so formed different views of well-being.

Other responses in all three surveys reinforced the notion that “harmonious relationships (‘spend time harmoniously with others around me’) were more important to people than “individual achievement”.

The evidence in this study, supported by other psychological studies suggests that:

… reducing an excessive focus on the individual self is one effective way to achieve happiness within material constraints …

Other studies have demonstrated that survey responses that suggest climate denial are highly correlated with respondents who are motivated by a sense of individualism.

Conversely, those who express a deep concern for the climate issue tend to be focused on community and family rather than the individual.

In Japan, there is a growing awareness of the attitudes held by the so-called – Satori generation (さとり世代) – “young Japanese who have seemingly achieved the Buddhist enlightened state free from material desires but who have in reality given up ambition and hope due to macro-economic trends.”

All the ambitions that capital has engendered to render us compliant, mass consumers are absent in the satori generation.

The members eschew: “earning money, career advancement, and conspicuous consumption, or even travel, hobbies and romantic relationships; their alcohol consumption is far lower than Japanese of earlier generations”.

In South Korea the same attitudes are held by the – N-po generation.

When I gave a presentation recently at the Rising Tide Coal Port Blockade in Newcastle I observed many young people who were dedicated to fighting against climate change and ending coal exports and who were seemingly of the ‘sartori generation’.

It gave me great hope.

The researchers say that being sartori is not because of ‘low income’ status but rather, “signifies a shift in mindset”.

What is the relevance of this type of research for articulating a degrowth strategy?

Quite clearly if there is a growing shift away from mass consumption and material aspiration (especially among the young) then the assumptions of the ‘green growthers’ fail.

If a growing number of people are being motivated to live “happy lives with less” material acquisitions and individual achievements then a viable political degrowth strategy is possible.

Conclusion

The next question that needs further work is whether this type of shift in attitude towards well-being is a Japanese (or Asian) phenomenon that is not evident in the advanced western nations.

Some research is emerging to suggest that the shift is generalising.

The clue is for the education system to change attitudes early.

oooooo

Fake news is not just the practise of the Right https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62292

Fake news is not just the practise of the Right

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62292)

January 13, 2025

The daily nonsense that economics journalists pump out in search of sales for their newspapers is nothing new and one would think I would be inured to it by now. But I still am amazed how the same old lies are peddled when the empirical world runs counter to the narratives. I know that the research in psychology has found that people save time by using ‘mental shortcuts’ in order to understand the world around them. Propositions that we ride with are rarely scrutinised in depth to test their veracity. Rules of thumb are commonly deployed to navigate the external world. And we are highly influenced by the concept of the ‘expert’ who has a PhD or something and talks a language we don’t really understand but attribute an authority to it. In the field of economics these tendencies are endemic. We are told, for example, that the Ivy league universities in the US or that Oxbridge in the UK, are where the elite of knowledge accumulation resides. So an economist from Harvard carries weight, whereas another economist from some state college somewhere is ignored. And once we start believing something, confirmation bias sets in and we ignore the empirical world and perspectives that differ from our own. The consequences of this capacity to believe things that are simply untrue his one of the reasons our human civilisation is failing and major catastrophes like the LA fires are increasingly being faced.

Progressives like to cite the proportion of statements from the incoming US President that are lies and rail against him for making out that it is the media that peddles ‘fake news’.

They approach this task with more than a touch of sanctimonious virtue and claim that it is domain of the Right and its media domination (Sky, Fox, etc) to behave in this outrageous way.

Yet, every day, the same progressives peddle ‘fake news’ in order to sell news.

For example, the weekend UK Guardian article (January 11, 2025) – If a Labour chancellor has to start cutting, keep calm. It’s not a betrayal – which attempts to justify more spending cuts from Rachel Reeves and warns the trade unions to behave, has all the overtones of the mid 1970s when the then Labour Chancellor Denis Healey lied to the British people about the country running out of its own currency and having to borrow from the IMF.

This is a classic example of ‘fake news’ and it is constantly peddled by those who would self-identify as being ‘progressive’ and antagonists of the Right.

My most recent in depth National Accounts analysis for the US was here – British GDP growth depends on the current fiscal position – a fact that is being forgotten (August 26, 2024).

As at the June-quarter 2024, the contribution from the public sector (both recurrent and capital expenditure) was 0.39 points to the 0.57 per cent growth recorded was obviously highly significant.

In the most recent data release for the September-quarter 2024, that contribution has declined to 0.16 points and GDP growth has declined to zero.

I also showed that if there is an external deficit, which for the UK has been constant since 1998, then the external sector is draining demand (spending) from the economy.

In the September-quarter 2024, the current account deficit rose to 2.8 per cent of GDP.

Export volumes fell for the third consecutive quarter while import volumes also fell, reflecting the weakening domestic demand.

The household saving ratio was slightly lower at 10.1 per cent compared to 10.3 per cent in the June-quarter, but still means that the household sector is spending only about 90 per cent of their disposable income and withdrawing the rest from the spending cycle.

If the overall private domestic sector desires to save overall (which is different to the household saving ratio being positive) then that also constitutes a net spending drain from the economy.

The only way the economy can then maintain positive growth is if the fiscal balance is in deficit and greater than the spending drains from the other two sectors.

The relatively large fiscal deficits in the UK during the GFC, provided the GDP (income) support for the private domestic sector to increase saving overall while the external sector was in deficit.

As the Tories pursued fiscal austerity in the period between the GFC and the pandemic, and the external balance moved into slightly higher deficit, the capacity of the private domestic sector to save overall vanished.

Private sector indebtedness rose substantially and was the only reason growth was possible in the face of the fiscal austerity .

That, of course is an unsustainable growth path because eventually the private balance sheets become too precarious and cuts backs in private spending are necessary to reduce the risk of insolvency.

With the external position still in deficit, any attempts by the Labour Government to reduce the discretionary fiscal deficit will be associated with a deterioration in the private domestic sector saving position.

Which means that the only way the British economy can sustain growth at present with the planned fiscal cutbacks is if the private domestic sector plunges into widening deficits and builds up ever increasing levels of debt.

That is not a smart national strategy.

Further, Britain is now performing worse than the major EU economies, which themselves are highly constrained as a result of not having their own currency and having Brussels imposing ridiculous fiscal rules which hamper government capacity.

The following graph compares GDP growth rates since the March-quarter 2023 to the September-quarter 2024.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The UK Guardian article thinks it is sensible to compare the UK, as a currency-issuer, with France, a currency-user constrained by EU fiscal dictates.

Such a comparison is common with the usual being some statement about not wanting ‘to end up like Greece, therefore austerity is imperative’ or similar.

All such comparisons are comparing two different monetary systems which are incommensurate in terms of the capacities of the national governments in question and are therefore not valid.

The commentators who make these comparisons clearly do not understand the difference which should disqualify them from making commentary in the first place.

Their readers are also none the wiser and just swallow the cant.

The UK Guardian article urges “Labour’s backbenches and … the big public sector unions” to “stay calm and and recognise that the UK is in a hole from which it will take years to emerge”, thus supporting the Chancellor as she contrives to cut spending in the UK.

Apparently:

Trade unions, in particular, need to dial down the rhetoric of betrayal should Rachel Reeves need to take a scalpel to departmental spending and delay eagerly awaited projects until she has the money to pay for them.

Well, my advice to the British unions is to defend the interests of your members and bring down any government that lies about not having “the money to pay for” progressive policies.

The unions should disassociate themselves from the British Labour Party both in terms of providing it with electoral funding and being compliant as the Labour government acts to undermine the prosperity of their members as it further lines the pockets of the ‘wealth shufflers’ in the City.

According to the journalist (Inman):

As looks increasingly likely, she will not have the funds this year after a dramatic slowdown in economic growth, more persistent inflation than was expected and a rise in borrowing costs.

Can you believe that?

All the fictional elements are there:

1. That the GDP slowdown is causing unemployment to rise so tax revenues are declining.

2. Higher interest rates have pushed bond yields up so the government is paying more on its outstanding debt than before.

Neither fact reduces the capacity of the British government to spend its own currency whenever it wants especially now that GDP growth is zero and heading towards recession (meaning there are available real resources that can be brought back into productive use with additional government spending).

The inflation rate has fallen significantly and is not persisting as a result of a chronic excess demand (spending) problem.

There is excess productive capacity, which means that there cannot be an overall excess demand.

Soon after that, another one of the classic fictions is paraded to the unwitting readers:

The Treasury’s independent forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), could say in its March review that all of Reeves’s financial buffer, set aside in the October budget as a cushion against a negative turn of events, has been eaten up, forcing the chancellor to revise her spending priorities.

Ignoring the fiction that the OBR is ‘independent’, here we have the recurring fiction that the currency-issuing government has to build up ‘stores’ of its own currency for rainy day events and when those ‘stores’ evaporate, the government has to reduce spending elsewhere.

Households, like you and me, have, if they are fortunate, what Keynes called ‘precautionary’ balances.

See this – Precautionary demand – for an explanation.

Basically, as a result of being financially constrained, households try to store up some saving to cover problems that arise in emergencies (health etc).

We have to do that because if such a calamity arises we want to be able to fix our car or repair our house or whatever.

But trying to transfer that concept and behaviour to a currency-issuing government has zero application.

Such a government has infinite minus a penny financial resources whenever it wants to draw on them.

No ‘stores’ of saving are required.

A stroke of a pen (or computer keypad) is all that is required.

The notion that there is some ‘buffer’ that the government needs for emergencies is used to justify unjustifiable austerity.

Just wait until the US government announces its financial support package for California – no stockpile of funds will be required.

The Federal Reserve will just clear all relevant accounts and the real resource assistance will flow.

The UK Guardian article’s conclusion is that:

With a steer from Treasury insiders who say that extra borrowing and higher taxes have been ruled out, spending cuts are the only option left on the table.

And that the unions etc should accept that and realise that “more borrowing to pay for public services” is not possible because the City will punish such an idea.

Please read my blog post – The British government does not have to appease the financial markets ( October 14, 2024) – for more discussion on why the proposition that the CIty can dominate the Government is preposterous.

To justify his claim, Inman looks over the Channel and says that Macron’s failed strategy (“a rise in debt to pay for increases in welfare and investment spending”) should be a warning to the UK.

Ridiculous.

France’s bond yields are rising because the debt it issues carries credit risk as a result of the nation using a foreign currency (the euro).

Further, France relies on the ECB to control bond yields and that organisation is not playing ball at present.

The UK is not remotely in the same situation.

The only similarity is that GDP growth is collapsing in both countries as the austerity sets in and while France is caught in that cycle by dent of its decision to surrender its currency and accept the fiscal rules, the British government has all the capacity it needs to break out of the decline.

But it seems intent on worsening the situation and the progressive media wants the unions and their members to comply.

The UK Guardian article also says that the options facing government are even more limited because:

From now on, the defence and NHS budgets will both need to rise quickly, putting the Treasury in a double bind. Where once it could rely on annual cuts in defence spending to pay for rising health costs, it must now look elsewhere.

Sure enough, spending on the NHS must rise to reverse the appalling situation created by 14 years of Tory mishandling.

And, of course, spending on defence does not preclude spending on other important areas that have been hollowed out by the Tories.

Conclusion

Fake news is not just the practise of the Right.

That is enough for today!

oooooo

Field trip to the Philippines – Report

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62312)

January 23, 2025

I have been working in Manila this week as part of a ‘knowledge sharing forum’ at the House of Representatives which was termed ‘Pathways to Progress Transforming the Philippine Economy’ that was run by the Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department, attached to the Congress (Government). I am also giving a presentation at De La Salle University on rogue monetary policy. It has been a very interesting week and I came in contact with several senior government officials and learned a lot about the way they think and do their daily jobs. I Hope the interactions (knowledge sharing) shifted their thinking a little and reorient to some extent the way they construct fiscal policy. This blog post reports (as far as I can given confidentiality) what went on at the Congress.

Ironically, I have been staying at a hotel that was built in 1976 to host the IMF/World Bank Annual Meeting in Manila.

It was the product of a massive government assistance to private property developers and construction companies.

Since then, the hotel has been the preferred choice when the top echelons of Chinese leadership including Xi Jinping, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin visit Manila.

Given that history I thought it was appropriate that I was housed there (-:

It is also adjacent to the central bank building (a huge complex) and the Department of Finance.

That also seemed appropriate (-:

And it is close to the waterfront promenade which is about the only place in the locality that one can go for long runs in the early morning without being killed by the manic traffic congestion in the Greater Manila area or die from exhaust poisoning.

But what might be a truly beautiful locality is somewhat neglected and rundown, which goes for much of the city and provides the government, in my view, with massive potential to create jobs to alleviate the chronic underemployment and poverty.

The Philippines is what world authorities call a middle-income nation.

In Manila, there are pockets of extreme wealth immediately adjacent to areas of crippling poverty where children lie in gutters absent from participation in education.

One runs past the highly protected Manila Yacht Club on the seafront where the marina seems to be housing some of the largest luxury boats one could ever see, and then immediately comes across countless people living in appalling conditions, who attempl to eke out survival selling all sorts of junk.

As an aside, in Melbourne, for example, I find younger people offer their seat of the trams to me in deference to my age, which still is a tradition in my home town.

The repsone to age in Manila appears to be hawkers coming up to me offering black market viagra for a few pesos (-:

Of course, I politely declined but wondered what visitors get up to in this city.

These hawkers are all over the place and one also regularly encounters very young children who come up and tug on your pockets seeking a few pesos.

It is almost Dickensian.

But it tells me there is tremendous scope for progress given the extent to which the nation is wasting its most valuable resources, a point I will return to.

The other thing that I have been musing about in relation to my current work on degrowth, delinking and breaking colonial dependencies is how far removed from such a narrative are nations such as the Philippines.

Everyone I have spoken to wants faster growth and material accumulation, which would be an outrageous aspiration in advanced nations but is perfectly understandable in the context of a nation like the Philippines.

Trying to bring those two ‘worlds’ together to save the planet is an almost insurmountable task and I will have further discussions today with officials to further understand this issue.

But walking through the streets of Manila – dodging traffic and motor cycles (and viagra sellers!) – the overwhelming feeling I have had is how far away from reaching a point where degrowth could become a topic of conversation in countries like this.

When I am living in Japan, it is easy to see such a narrative emerging.

But in Manila, it seems like a road to far.

That is a challenging thought.

On Wednesday (January 22, 2025), I travelled out to the House of Representatives complex near Quezon City, which is a 25 kms journey that can take two hours or so given the traffic congestion.

I was invited to come to the Philippines to speak at the workshop organised by the CPBRD of the House of Representatives.

My friend, Professor Jesus Felipe also spoke. He worked at the Asian Development Bank for many years and is now at De La Salle University in Manila.

In the past, we have worked together on ADB sponsored projects studying economic development in Central Asia and Pakistan and so we have a long working association.

The meeting was attended by more than 100 senior officials from the major economic policy areas of government – Central Bank (BSP), Department of Finance, Department of Treasury, Department of Budget Management, and other related policy making departments and economic research institutes.

These are the people who design and implement economic policy in the Philippines and so it was a really good chance to talk to those who influence things here in one room rather than having separate meetings which would have been impossible.

In his introduction, Jesus laid out the fundamentals of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) given that the Philippines has its own currency and floats it on international markets.

That introduction laid the foundations for my presentation, which began by noting that at the end of December 2024, the Secretary of Finance, Mr Recto (they call the responsible portfolio Minister Secretaries here in the way the US government categorises these positions) released the 2025 fiscal statement – Recto: PHP 6.326 trillion national budget for 2025 most powerful tool to deliver the biggest economic benefits to Filipinos, reaffirms DOF’s commitment to work hard in funding it.

The statement launched a 6.3 trillion peso national spending initiative which represented a 9.3 per cent growth in appropriations.

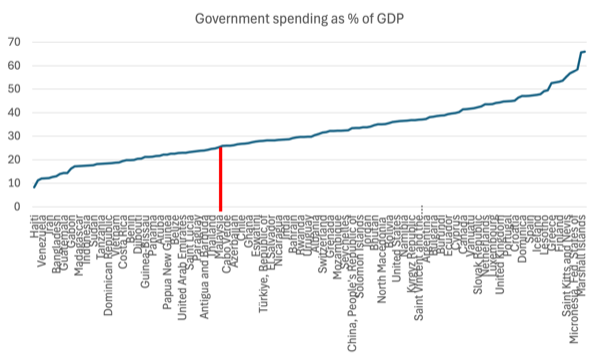

Government spending will constitute around 22 per cent of GDP in 2025, which the officials believe represents ‘big government’.

I pointed out that this was actually a fairly modest government footprint relative to other nations.

Consult the data – Government expenditure, percent of GDP – to see the point.

Out of 152 nations for which the IMF supplies this measure, the Philippines is standing at rank 53 (from smallest to largest) – so there are about 100 nations that have larger government sectors.

The following graph shows the distribution of the 152 nations and the vertical line demarcates the Philippines.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Surrounding the Philippines (in percentage of GDP) are

Qatar 24.3 per cent

Thailand 24.6 per cent

Cambodia 24.8 per cent

Malaysia 25.3 per cent

Philippines 25.9 per cent

Cabo Verde 26.0 per cent

Togo 26.0 per cent

Azerbaijan 26.2 per cent

Senegal 26.6 per cent

Chile 26.8 per cent

The Bahamas 26.9 per cent

The point is that perceptions are very significant influences on how policy makers think and in this case, the ‘belief’ that the government sector has a ‘large footprint’ when in fact it is relatively small, is an important ‘noise’ in the discussions.

The Secretary’s statement noted that of the 6.4 trillion national budget for 2025, 4.64 trillion was being supported by revenues, which is framing that conditioned my following discussion.

The statement also noted:

Secretary Recto reassured the public that the DOF will ensure that the country has enough funds to meet its needs and that every centavo will be spent efficiently on programs and projects that will greatly benefit the people.

And:

He emphasized that the DOF will strive to not just meet but exceed its revenue targets to generate more resources—just as the country’s strong fiscal performance this year has demonstrated.

In my slide I highlighted:

– “the country has enough funds”

= “to generate more resources”

– “strong fiscal performance”

And then posed the following questions:

1. What does “supported by revenues” mean?

2. What does “ensure the country has enough funds” mean?

3. What does “to generate more resources” mean?

4. What is a “strong fiscal performance” mean?

5. Most important question: Is this a full employment fiscal policy or not?

Those questions provided the talking points to further illustrate the essential differences to the way an MMT economists thinks and the mainstream framing.

The Philippines issues its own currency and has ‘infinity minus a peso’ spending capacity in financial terms.

So it makes no sense to spend a second considering that the government might not have enough funds (of its own currency) or by framing the fiscal challenge in terms of proportions of the total spending commitment that is ‘supported by revenue’.

Further, the focus on financial resources diverts attention from the real challenge – utilising the productive resources that are available effectively.

The day before the workshop I had taken a long walk (several kms) through the city and I saw a lot of ‘wasted resources’ – principally the citizens in the informal economy living in poverty with little work and shelter.

Generations of Filipinos in the streets and the children not in school and begging for pesos.

In the discussion yesterday, an official claimed that there was no fiscal space for the government because ‘everybody accepted’ that the nation was at full employment.

It was a stunning observation after what I saw the day before in the streets.

The official unemployment rate is low – true.

But even the official data shows that there are 15 per cent of the survey underemployed.

And 30 per cent of those classified as employees in the official data are classified as working in ‘Elementary Occupations’ – which are precarious, low-paid, and low-productivity activities.

But more stark is the fact that around 80 per cent of total ’employment’ is in the informal economy, not captured in the official data that is collected using the ILO’s Labour Force framework.

So to think that the nation is remotely close to operating at full employment is crazy and the problem is that that misperception or accepted version conditions the policy choices.

Which, in my view is why there is so much resource waste here and so much poverty.

For a few pesos, the government could make a massive difference to the lives of the poorest citizens.

In this context, I asked the following questions:

1. Why hasn’t the fiscal policy plan outlined a major public sector job creation program.

2. Why not provide jobs at least at a socially inclusive minimum wage?

3. Why not provide full-time positions to eliminate underemployment?

4. Why not provide training ladders within the jobs to increase skills?

The officials said there were some job creation schemes, but when one examines them it is clear they are small and do little to solve the national problem, even if they help the participants individually.

What they indicate is that scaling up these interventions would deliver massive benefits to the population and would provide a real chance to reduce the poverty and resource wastage.

The government’s aspirations are to create high-level manufacturing industries (become a leading producer of EVs, for example), but in my view they are a distance away from having the capacity to achieve that aim and would get much larger immediate returns by starting with job creation prograns in the areas where abject poverty is the defining characteristic.

There urban areas need significant work to improve the quality of life – starting with cleaning the streets and the drains and the waterways.

When I go out running I see tens of thousands of jobs that could be relatively easily offered which would radicalise the local environment and improve the living standards here.

That would be a good place to start but the national fiscal statement did not allow for any such intervention.

I also discussed the proposition that the limited social security system here would soon ‘run out of funds’.

This is a repeating claim and is nonsensical.

The system, which is characterised by several different funds, has several problems, including low coverage and need to expand coverage and improve benefits.

But the schemes can never ‘run out of money’ unless the national government chooses that option for political purposes.

Spending precious time debating endless actuarial assessments that produce elaborate graphs showing insolvency points diverts the officials from the actual challenge.

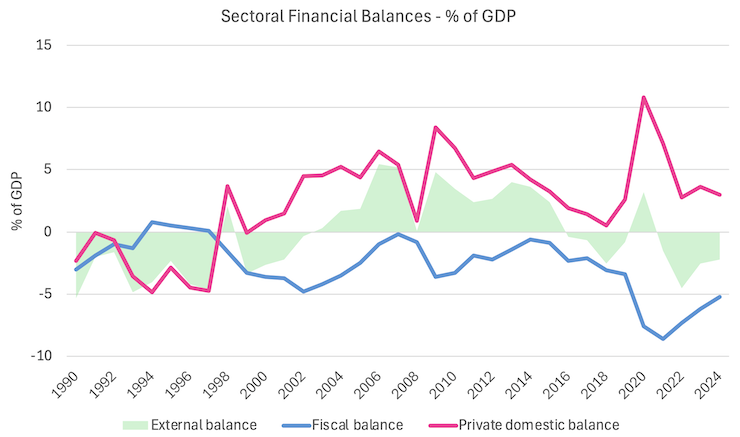

I used this graph which shows the financial balances of the government, external and private domestic sectors from 1990 to 2024 to illustrate some essential points.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

It allows us to understand that when fiscal policy shifts, the private domestic sector’s financial balance shifts more or less in the opposite direction, if the external sector balance is relatively stable.

It also helps start a narrative about what happens when governments seek to reduce the fiscal deficit – which is the medium-term aim of the government.

Clearly, after the pandemic support, the government is now trying to reduce its fiscal position and that is forcing the private domestic sector towards deficit.

Such a growth strategy is ultimately unsustainable and there is evidence that private debt in the Philippines has grown substantially in the last several years.

Ultimately, the increasing precariousness of the private balance sheets will lead to a correction (spending reduction) and then the country heads to recession and the government is forced to increase its fiscal deficit.

I noted this allows us to differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ fiscal deficits.

A ‘good’ deficit results when the government fills the non-government spending gap to push the economy to full employment.

A ‘bad’ deficit is when the government tries to move towards surplus and the fiscal drag does not match the spending and saving desires of the non-government sector, and the resulting recession reduces tax revenue and forces the government to increase welfare outlays, which ultimately see the fiscal deficit increasing.

That led to a lot of discussion in the Q&A section of the workshop and prompted the ‘full employment’ comment I noted above.

The reality is that there is significant ‘fiscal space’ in terms of idle real resources in this country and denying that reality leads the policy makers down unproductive deads ends that spend time talking about financial ratio while ‘Rome burns’.

I also discussed the national debt issue and noted that during the early years of the pandemic the BSP basically credited bank accounts on behalf of the fiscal departments to fund the policy interventions.

For eample, on March 23, 2020, the BSP purchased PHP300 billion BTr bonds and on March 26, 2020 it remitted PHP20 billion to the Treasury as dividends on the large holdings of government bonds held by the central bank (BSP).

This was a case of the government lending to itself.

Right pocket sells bonds to the left pocket and pays the left pocket interest returns, which are then remitted back to the right pocket of government as dividends.

It is an elaborate accounting charade that attempts to hide the reality that the government is just spending its own currency and does not need tax revenue or debt issuance to ‘raise funds’.

In that context, I asked the officials the following questions:

1. What does it mean for government debt to be ‘manageable’ (a term used by an official report when the rising public debt level was being scrutinised in recent years)?

2. What would happen if the government stopped issuing debt that is denominated in foreign currencies? (Around 35 per cent of total public debt is such and exposes the country to the vagaries of export markets – totally unnecessary).

3. What would happen if the Department of Finance simply stopped issuing long- and short-term domestic debt and instructed the BSP to see all government payments were cleared (think March 2020)?

4. What were the consequences of the government just lending to itself during the pandemic – good or bad?

5. What would happen if it simply wrote all of its government debt holdings off?

6. Who would notice?

Those questions prompted a lot of discussion.

Finally, at the end of the workshop, an official from the Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (Mr Aquino) presented me with the following gift:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Which characterised the tremendous warmth and hospitality that everyone has given me during my stay here for which I am very appreciative.

Conclusion

Today I am off to the local university to present a seminar on why New Keynesian monetary policy prioritisation is a failed policy strategy.

Unlike yesterday, today will be a different type of talk, technical and academic

oooooo