@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

‘Finding the Money’ The Documentary That Has DC POWER Brokers On Edge https://youtu.be/s6QccvybP6I?si=_23V2Fp29J4sio3J

‘Finding the Money’ The Documentary That Has DC POWER Brokers On Edge

Jessica Burbank and Amber Duke discuss the documentary “Finding the Money,” which chronicles

ooo

‘Finding the Money’ The Documentary That Has DC POWER Brokers On Edge

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6QccvybP6I)

Jessica Burbank and Amber Duke discuss the documentary “Finding the Money,” which chronicles the U.S. monetary system. The hosts chat with the film’s impact is director Maren Poitras. #FindingTheMoney #economy

Transkripzioa:

0:04

a new documentary is stirring the pot in

0:07

DC in a major way Biden’s top economic

0:09

adviser Jared Bernstein is apparently

0:11

uncertain about how our monetary system

0:13

works along with other mainstream

0:16

economists the US government can’t go

0:18

bankrupt because we can print our own

0:21

money it obviously begs the question why

0:24

exactly are we borrowing in a currency

0:26

that we print ourselves I’m waiting for

0:28

someone to stand up and say why do we

0:31

borrow our own currency in the first

0:34

place like you said they print the

0:36

dollar so why why does the government

0:38

even borrow well

0:41

um the uh so the I mean again some of

0:47

this stuff gets some of the language

0:50

that the mm some of the language and

0:52

concepts are just

0:53

confusing mainstream economists not

0:56

understanding the monetary system isn’t

0:57

the only reason the film is Raising

0:59

eyebrows it’s centered around answering

1:01

the question asked time and again in DC

1:03

you want Healthcare student loan debt

1:06

cancellation Social Security how are you

1:08

going to pay for it it seems people are

1:11

interested in the answer within one day

1:13

of its release finding the money Rose to

1:15

number one on the documentary charts of

1:17

Apple TV of course people are interested

1:20

because every few years we are

1:22

threatened with a looming government

1:23

shutdown because Congress is in a fight

1:25

over budgeting and inevitably we hear

1:28

about how we have to cut the national

1:30

debt and reduce the deficit the movie

1:32

star Stephanie keelton has angered some

1:35

of the most powerful economists and

1:36

policy makers in the country by arguing

1:39

convincingly that they’ve got it all

1:40

wrong here to discuss the film’s impact

1:43

is director Marin pois thank you so much

1:46

for joining us so let’s start with a

Why does the government borrow money

1:49

little just a little bit on that Viral

1:51

clip I know we don’t want to rub it in

1:52

too much but I mean the question he was

1:54

asked of course is why does the

1:56

government borrow money if they can

1:58

print their own was there anyone that

1:59

you talked to for the film that had a

2:01

convincing answer well no and I think

2:04

that’s that’s the exact point is it’s

2:05

not about one person it’s not about an

2:07

aberration I think what I was trying to

2:09

explore in the film was again I came

2:11

across this kind of small group of

2:12

heterodox economists um or Renegade

2:15

economists who are making some striking

2:18

uh you know assertions that the that the

2:20

mainstream of the field of Economics

2:22

might be missing some fundamental

2:24

assumptions around the nature of money

2:26

uh where money comes from and therefore

2:29

the nature of the debt and what the

2:30

national debt is what the federal

2:32

government can afford and so these were

2:33

bold assumptions and as a filmmaker as a

2:35

journalist I wanted to explore them and

2:37

kind of tease out the conflict there and

2:38

the controversy because there is a lot

2:40

of that and the mainstream will point to

2:42

this smaller group referred to as modern

2:44

monetary Theory as saying oh this is

2:46

voodoo economics this is a crackpot

2:48

Theory but they they start from the

2:51

simple premise or the simple observation

2:53

that the federal government is the

2:54

issuer of the currency of the US dollar

2:57

and has been since the Constitution

2:59

Congress

3:00

so starting from that basic premise U my

3:03

question was could it be that mainstream

3:05

economics hasn’t integrated that

3:07

observation into their their field into

3:10

their models into how they predict and

3:12

understand what the national debt is and

3:14

what the federal government can afford

3:16

and so I wanted to try to find out for

3:18

myself you know what do mainstream

3:19

economists think can they show me

3:21

exactly where this Renegade or smaller

3:23

heterodox Theory goes wrong um and so so

3:27

you see some of that in the film and and

3:29

I tried to talk to the broadest range of

3:30

economists that I could um and so that

3:32

includes Jared Bernstein and many others

3:34

and what was so striking for me and so

3:36

educational for me in that clip was to

3:38

see that he hadn’t been asked that

3:40

question before from another journalist

3:43

in the textbooks or him himself he

3:45

hadn’t asked that question to himself

3:47

and that’s what I think is the most

3:49

interesting and the most educational for

3:51

me was could it be that that kind of a

3:53

basic question hasn’t been asked or you

3:56

know because I always thought okay I’ll

3:57

I’ll I’ll go to the mainstream Economist

3:59

and they’ll simply explain to me why

4:00

this small group is wrong but but I

4:02

didn’t get that I didn’t get a

4:04

convincing explanation of someone

4:06

showing me specifically where the theory

4:08

goes wrong and I think that’s what you

4:10

see the characters in the film go

4:12

through as well Stephanie Kelton in the

4:14

film starts out skeptical everyone I met

4:16

who’s come to the theory has started out

4:18

skeptical myself included right because

4:21

it bucks conventional wisdom we’re

4:23

taught the federal government in order

4:25

to spend has to go out and find the

4:26

money it has to tax and it has to borrow

4:29

in order to spend this Theory modern

4:32

monetary theory is saying it’s the other

4:34

way around there’s a different order

4:35

that’s going on here and so if we go

4:37

back to look at that you know what does

4:39

that mean for the bigger ramifications

4:41

of what is the debt and what can the

4:42

federal government afford and so you

4:45

know long story short I think I

4:48

Stephanie and the film and myself are

4:50

starting to to be more convinced once we

4:52

look into the actual operations we look

4:54

at the the talk to the you know Federal

4:56

Reserve and the treasury of how does the

4:58

operations occur what are the

5:00

what are the funding mechanisms and the

5:01

order of operations of how our monetary

5:04

system currently operates and when you

5:06

dive into that I think you get different

5:09

answers and maybe what’s included in the

5:10

textbooks so now the question is you

5:12

know can we change can we change the

5:14

textbooks right and we need to I studied

5:17

public policy at Brown University we

5:18

didn’t touch money creation which is an

5:21

essential component of a growing economy

5:23

where is money entering it from the

5:25

private sector from the federal

5:26

government you know foreign debt would

5:28

be the other option the foreign sector

5:30

and really what this documentary does is

5:32

fill in that blank that’s not just a

5:34

blank in most of the Public’s minds but

5:36

honestly most of the academics Minds as

5:38

well which is why I think mainstream

5:40

economists don’t have answers to these

5:42

questions about mmt because it’s filling

5:44

a gap in the field of economics and

5:46

public policy so can you tell us about

5:48

just the importance of the magnitude of

5:51

what’s exposed in this film turning the

5:53

conventional wisdom on its head and

5:56

offering a in my opinion a very

5:58

accessible explanation well thank you

6:00

and yes I think you know the

6:01

ramifications are quite large and that

6:03

was why you know I had to try to take it

6:04

on because it’s not just an academic

6:06

debate that’s hidden you know in

6:08

Academia that can be hashed out over

6:10

there it’s like this affects all of our

6:12

daily lives and really the future of the

6:13

planet you know when we’re thinking

6:15

about climate and and we’re always asked

6:17

you know how can we afford this climate

6:18

spending um or the trillions of dollars

6:20

we need you know there’s no government

6:22

in the world according to John Cary who

6:24

has the doll you know who has the money

6:26

to spend to avert climate change um and

6:29

so not only that but just how can we

6:31

actually budget how can the government

6:33

budget more responsibly and that means

6:35

looking at our real resources so I think

6:37

the real ramification here is that we’re

6:39

budgeting for the wrong thing we’re

6:41

thinking that money is the real scarce

6:43

resource itself that we need to budget

6:45

and conserve when really there are of

6:47

course limits right the government must

6:49

prioritize it must still budget but if

6:51

we’re budgeting for money money is just

6:53

the organizing tool of the real

6:56

resources the real resour sources in our

6:58

economy are what we need to be budgeting

7:00

for and conserving for future

7:02

Generations you know we hear the

7:03

national debt is this terrible burden

7:05

for future Generations but what are we

7:07

really leaving them in terms of real

7:09

wealth and real resources and that’s

7:10

what the government needs to be

7:12

considering and budgeting for and of

7:14

course that’s tied to inflation and

7:16

inflationary limits so the federal

7:18

government has a responsibility to

7:20

budget um and any new spending proposal

7:23

should be analyzed for its inflationary

7:26

potential and its real resource use and

7:29

those are those are linked and so what I

7:31

think this school is trying to bring is

7:33

actually a more sophisticated or a

7:34

better public debate around how can we

7:37

budget more responsibly how can we

7:38

ensure that we’re preventing inflation

7:41

and that’s tied to real resources and

7:43

real resource use so those are the

7:45

limits we need to be thinking about but

7:47

when we’re budgeting in terms of money

7:49

we we miss spending that may be a lot

7:51

more affordable that our society can

7:53

afford you know on a societal level so

7:55

what’s exciting to me is it could mean

7:57

that certain types of spending that

7:59

maybe cost a lot of dollars but don’t

8:01

cost a lot of resources become more

8:04

affordable so so certain types of

8:05

spending on on climate or on you know

8:08

employing people who are currently

8:09

unemployed to restore forests and

8:12

wetlands and Fisheries um that’s

8:14

preserving and and increasing our real

8:17

resource capacity the real resources

8:19

that we have um and it doesn’t cost

8:22

Society you know to employ people who

8:23

are currently unemployed and create this

8:25

net benefit sure some dollars are spent

8:29

but we haven’t we’ve we’ve net gained as

8:31

a society and and I think that

8:32

translates to other aspects of our

8:34

economy as well so healthc care you know

8:37

what can medic is Medicare for all

8:39

actually does it cost Society less

8:41

overall in terms of real resource use um

8:44

labor use and so if we’re moving some

8:47

dollars onto the federal budget that

8:49

doesn’t necessar you know that actually

8:51

means it could be disinflationary or

8:53

deflationary if we move to a system that

8:55

uses less resources so Medicare for all

8:57

it costs Society overall less um so I

9:01

think that’s really a different

9:02

perspective because we’re just focused

9:04

on the dollars we think that’s that’s a

9:06

that’s a lot of government spending but

9:07

we have to look at the societal

9:09

perspective and spending overall in the

9:10

economy so it’s Healthcare it’s you know

9:13

it’s it’s energy it’s it’s our public

9:15

transit system you know a public transit

9:17

system that’s fast free and reliable

9:19

cost Society a lot less resources than

9:21

the current you know car infrastructure

9:23

that that we have and that we’ve

9:24

invested in um and you can look at you

9:27

know energy utilities and public

9:28

provisioning of green renewable energy

9:31

that can cost consumers less right and

9:33

if the way we do it today with with

9:35

private energy utilities they have no

9:37

incentive to invest in the green

9:39

renewable energy because they don’t want

9:41

to you know bring costs down for

9:42

consumers um then that would eat into

9:44

their profits right they want to keep

9:46

prices going up so if if government is

9:48

able to spend some dollars to provide

9:51

you know good clean renewable energy we

9:54

can look at how do we bring costs down

9:56

for everyone and and do things more

9:57

efficiently so the point is it it is a

10:00

bit of a paradigm shift in how we have

10:01

to think about federal government

10:03

budgeting and hopefully in a more

10:04

sophisticated way Stephanie’s better at

10:06

doing this than me but I always say do

10:08

you feel better about dollars entering

10:10

the economy from a huge private bank

10:12

with a charter versus the federal

10:14

government because it’s really going to

10:15

be this big entity and a lot of those

10:17

guys in my view are on the same team but

10:19

uh you know Stephanie has been so

10:21

essential in addressing a lot of the

10:23

stuff about mmt that’s out there like

10:25

you guys are saying we can just print

10:26

money endlessly and there are no

10:28

constraints can you talk about her voice

10:30

and Mission yeah and so right that’s

10:32

kind of the misperception when I went

10:34

out to go talk to Economist where does

10:35

mmt go wrong and they’ll say well mmt

10:37

says you can print infinite amounts of

10:39

money and never cause inflation so

10:41

that’s not what mmt says that’s not an

10:43

useful debate or an useful critique if

10:46

you’re critiquing that statement right

10:47

mmt will say you can print or create as

10:50

many dollars as you want um but there

10:53

are consequences you will run into

10:55

inflationary and real resource limits

10:57

and that’s what you need to be thinking

10:58

about not the national debt or a debt

11:02

crisis or spiking interest rates as what

11:04

we see in the textbook and what we see

11:06

you know hearing after hearing on the

11:07

hill is you know the dangers of the

11:09

national debt uh and how CBO the

11:11

Congressional budget office analyzes

11:13

legislation it only looks at how many

11:15

dollars does it add to the federal debt

11:17

and projects that out over time and and

11:20

fears of of a debt crisis but if if we

11:23

step back and break down starting from

11:25

the assumption that the federal

11:27

government is the issue of the currency

11:29

what is the national debt then right and

11:31

and that goes back to the original

11:33

question and and rather than the

11:35

national debt being uh the a record of

11:38

the number of dollars the federal

11:39

government has borrowed it’s really more

11:42

accurate to say the national debt is a

11:44

record of the number of dollars the

11:45

federal government has created and spent

11:48

into the economy and not yet taxed back

11:50

so it’s the dollars that we hold in our

11:52

pocket and in our bank accounts um and

11:55

then the government voluntarily uh

11:57

offers to issue bonds

11:59

uh really but the key is that it it’s

12:01

voluntary to switch out those dollars

12:04

for interest bearing dollars which you

12:06

can call treasury bonds or bills or

12:08

notes and the important distinction that

12:10

mmt is able to make is that that’s not a

12:13

financial necessity it’s not what we

12:15

should call a borrowing operation in

12:18

order that they’re not going out to find

12:19

money to borrow in order to spend but

12:22

it’s a voluntary operation where they’ve

12:24

already spent so that goes back to the

12:26

order if you’re the issue of the

12:28

currency before anyone can have dollars

12:30

to tax for the government to tax or or

12:33

to borrow from you know where do where

12:35

do those dollars come from in the first

12:37

instance right and that’s the important

12:39

question that you know we kind of just

12:41

we live in the moment today and that we

12:43

see the taxing and the borrowing

12:44

happening and you can kind of get

12:46

confused but if you go back to the

12:47

beginning maybe you can see the order a

12:49

little more clearly and in the film you

12:51

know we bring in a lot of historical

12:52

examples and so I think that’s important

12:54

just to clarify the order if the

12:57

government has to spend first

12:59

before it can tax from you or from me

13:02

what does that mean and what does that

13:03

mean the national the national debt is

13:06

and so it so it changes again going back

13:08

to the limits the national debt um not

13:11

being a record of dollars borrowed that

13:13

we have to pay interest on and that

13:15

future Generations owe it’s it’s

13:17

literally the opposite it’s it’s the

13:19

dollars we have in our pockets that is

13:21

the asset the financial asset of future

13:23

Generations um so again the limit to how

13:26

much you can spend and the is inflation

13:29

and real resource limits so not that

13:31

dollar limit um so so yes so it is that

13:34

that Paradigm Shift um but there’s a lot

13:35

of a lot of places where this can go and

13:38

a lot of qu more questions than answers

13:40

maybe that this all brings up like why

13:42

why are we issuing bonds what is the

13:43

role of interest rates um why are we

13:45

paying almost a trillion dollars in

13:47

interest today um eating into you know a

13:50

trillion dollars is now being of new

13:53

money you can call it is being created

13:55

and spent given to bond holders um at 5%

13:59

interest for the privilege of already

14:01

having dollars they get 5% more um for

14:05

for yeah the benefit of of having

14:07

dollars in proportion to how many they

14:08

have and that is supposed to be the

14:10

Federal reserve’s Tool to to lower to

14:13

damp down inflation um but I think we

14:15

need to question that by going back to

14:17

looking at what are the operations

14:19

what’s actually happening on the

14:21

operational level who’s getting what

14:23

money and those are in the end political

14:26

choices yeah speaking of I mean the infl

14:28

infl AR limits I’m kind of mind blown

14:30

that that wasn’t one of the first

14:32

critiques brought up by Bernstein and

14:34

and the other people that you talked to

14:35

in the film I mean I’m not an expert but

14:37

I have an economics degree and it’s a

14:39

basic fundamental you know part of

14:41

Economics that if you print too much you

14:44

can cause inflation and um the fact that

14:47

they didn’t mention that is again very

14:49

confusing and seems like it would be a

14:51

basic concept and I’m glad that you

14:52

acknowledge that you can’t just print

14:54

with with Reckless abandoned without

14:56

having consequences to that um what was

14:59

the reaction then to this film and some

15:02

of the concepts that were put out during

15:04

a period where we are struggling a lot

15:06

with inflation right I mean there was a

15:07

lot of money pushed out by the federal

15:09

government during the pandemic we hit a

15:11

peak of somewhere between 9 and 10% of

15:13

inflation during the biding

15:14

Administration it’s come back down to

15:16

around 3% but people are still really

15:18

struggling so I mean how open do you

15:20

think people are to a monetary Theory

15:23

like this when they’re seeing the

15:24

ramifications of that yeah exactly and I

15:27

think you know that’s why it’s so

15:28

important to tease out what does cause

15:30

inflation and what were the causes of

15:32

any specific inflationary episodes so

15:35

going back to co the covid-19 pandemic

15:37

or going back to the 70s or other you

15:39

know inflationary episodes we have to

15:40

look at what are the causes um because I

15:43

think it’s too simplistic to say dollars

15:45

go up inflation goes up the the economy

15:48

is more complex than that there are

15:50

different sectors and so it’s about and

15:53

it’s about spending so when we look at

15:55

the government it’s about what are they

15:56

spending on are those resources is

15:59

available if they want to spend on

16:01

Healthcare if they want to spend on

16:02

green energy they have to go out and see

16:04

like are is the labor there you know do

16:07

we have doctors and nurses to to be able

16:09

to hire or is that going to drive up

16:11

wages and prices or you know we have to

16:14

look at sector specific spending and so

16:16

what happened with the covid pandemic of

16:18

course was we had an increase in

16:20

government spending but that didn’t

16:22

necessarily mean that that was the cause

16:24

of the inflation so we have to that just

16:26

kind of filled out the I think the drop

16:28

huge drop in private spending that we

16:30

saw right after covid-19 hit um

16:32

government spending was able to come in

16:34

and backfill that loss of private

16:36

spending so that people didn’t lose

16:38

their jobs didn’t lose their homes this

16:39

time as compared to 2008 um and then the

16:43

FED itself and central banks around the

16:45

world have done great great analysis to

16:47

show you know what what are the causes

16:49

of this inflation what are the sectors

16:51

where we see the inflation occurring and

16:53

you know in the US it started with with

16:55

computer chips and shutting down car

16:57

factories and then the rise in used car

17:00

prices because all of a sudden you know

17:02

you have the shortage of cars and that

17:03

was the first thing to hit the CPI or

17:05

the inflation index and that’s a very

17:07

specific cause right and so how do you

17:09

address that inflationary pressure well

17:12

you have to look at the supply of

17:13

computer chips and that’s actually

17:15

exactly what the Biden Administration

17:16

did with the chips and Sciences act they

17:18

passed a bill to spend new money to

17:21

address the capacity in this bottleneck

17:24

this Supply you know this kind of

17:26

friction overheating we see in coming

17:29

from computer chips so they said we need

17:31

to actually produce some computer chips

17:32

here at home for strategic reasons today

17:34

they mostly all come from Taiwan so they

17:37

they’ve invested now to produce more

17:38

here so that we don’t hopefully hit that

17:40

inflationary bottleneck again and so

17:42

that’s the counterintuitive way that we

17:44

need to understand inflation is

17:46

sometimes it takes additional spending

17:48

if it’s a supply constraint um you know

17:51

and then with the rest of the pandemic

17:52

we did see other Supply shocks and so

17:55

there’s a lot going on there but then

17:56

you get into oil or energy with you know

17:59

the war in Ukraine we saw a big oil

18:01

price shock uh how do you address

18:03

something like that or something similar

18:04

that happened in the 1970s well you have

18:06

to address the energy sector you know

18:08

the again the FED we’ve given all the

18:11

power to or you know we’ve given the all

18:12

the responsibility for dealing with

18:14

inflation to the Federal Reserve and

18:16

they only have one tool they only have

18:18

the interest rate and so that’s all they

18:20

can do is raise the interest rate to

18:21

fight inflation even if their own models

18:24

their own economists are telling them

18:26

this is not going to be effective in

18:27

this type of inflation and maybe is

18:30

never effective for for any type of

18:32

inflation they just don’t have the

18:33

empirical evidence and and you can ask

18:35

them as well you know show me the

18:36

published papers that show that raising

18:38

the interest rate is going to lower

18:40

inflation so so yes so there’s a lot

18:43

there’s a lot to discuss but it’s the

18:45

main point is it’s very important to

18:47

look at what are the causes of the

18:48

inflation what are the the Myriad tools

18:50

and policies that we can put in place to

18:52

address that specific inflation because

18:54

otherwise you’re not getting to the root

18:56

of the problem and we got to get to the

18:57

root of the problem and I think what mmt

18:58

does is it centers inflation risk takes

19:01

it more seriously says we need to be

19:03

planning and and preventing inflation

19:06

before we spend as well as employing

19:08

tools after inflation pops up to prevent

19:10

it and they centering that in their

19:12

Theory it’s not an afterthought you know

19:14

it’s the center and something that’s

19:15

been essential among mmers that I think

19:18

has given them a lot of credentials at a

19:21

time when everyone was questioning them

19:23

and I would say people were questioning

19:24

the mmt community because you know it it

19:27

does question the status quo in a major

19:30

way the tool of adjusting uh interest

19:33

rates to manage the unemployed

19:35

population has largely been used to keep

19:37

wages down and since nairu which is the

19:39

policy at the Federal Reserve where they

19:41

set this magic number that they think

19:44

you know unemployment should be at to

19:46

curb inflation Drome Powell’s admitted

19:49

on the floor of Congress that they’re

19:50

getting it wrong and they don’t have

19:51

evidence to back it up and the

19:52

relationship’s not strong as it used to

19:54

be 50 years ago but since nairo was

19:56

enacted in the 70s that is really when

19:59

we saw wages start to depart from

20:02

productivity and so in part this has

20:05

been used as a tool to keep wages low

20:07

that really benefits corporations So

20:08

when you say that actually isn’t

20:10

necessary uh to keep people unemployed

20:13

and we can free up Capital we talk all

20:15

about how’s gridlock in Congress and

20:17

that’s why not a lot gets done but

20:19

they’re really leaving this power of the

20:21

purse on the table by not moving in the

20:24

direction that mmt lays out of here are

20:26

the real constraints of inflation we’ve

20:29

predicted recessions before based on

20:31

this economic thinking do you think you

20:34

know the film is going to help people

20:36

start take it seriously because it’s

20:37

kind of undeniable even if you’re not an

20:40

economist to watch the film and change

20:42

your opinion so yeah I think the the

20:44

basis here is that we we are allowed to

20:46

question um e economics because I think

20:49

a lot of these bigger questions actually

20:51

are political questions around who gets

20:54

what resources and that’s what economics

20:56

comes down to it’s not really these

20:58

natural inevitabilities that the rich

20:59

are going to get richer and the poor are

21:01

going to get poorer we’ve created this

21:02

thing we call the economy humans create

21:05

this thing we call money it’s an

21:07

organizing tool for the real resources

21:09

we have and if we look at it that way we

21:11

realize that these are fundamentally

21:12

public policy decisions political

21:15

choices that I think as voters in an

21:17

economy we all need to have some basic

21:19

understanding of in order to vote for

21:20

what we want or the public interest that

21:22

we want to prioritize and so I hope that

21:25

that’s where it brings this debate and

21:26

it brings it to you know a little bit

21:28

more sophisticated and more serious

21:30

debate around what can we really afford

21:32

and what could we prioritize in terms of

21:35

future Generations leaving them the real

21:37

resources and the planet and and a and a

21:39

functioning economy that benefits us all

21:42

uh would be the Hope Marin Poes thank

21:44

you so much for joining us today we’re

21:46

going to be back with more Rising after

21:47

this

21:53

[Music]

oooooo

MTM euskaraz (Moneta-Teoria Modernoa) edo MMT ingelesez (Modern Monetary Theory).

Teoria berri horren fathers hauxek dira: Warren Mosler, Bill Mitchell eta Randall Wray.

Hirurak oso aipatuak eta ezagunak (?) dira UEU-ko blog honetan…

Hona hemen Bill Mitchell-en bi lantxo:

Bill Mitchell, bi lan

1) Bill Mitchell: Ekonomialari gehiago ari dira Britainiar gobernuari kritika egiten

Monday’s blog post (23/09) is now posted (17:01 EAST) – More economists are now criticising the British government’s fiscal rules – including those who influenced their design – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62019 #mmt

ooo

More economists are now criticising the British government’s fiscal rules – including those who influenced their design

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62019)

September 23, 2024

There is renewed debate in Britain at present on the use and design of the new government’s fiscal rules, which many people are now saying will force expenditure cuts which will “damage the ‘foundations of the economy”, according to the Financial Times article (September 16, 2024) – UK spending cuts would damage ‘foundations of the economy’, Reeves told. Those reported ‘telling’ Reeves include British economists, who were instrumental in the design of the rules that the new Chancellor has taken on and deemed necessary to rigidly control government spending. The economists claim that if Reeves continues to operate according to the fiscal rule “inherited by the Labour government” it will cut public investment expenditure significantly and undermine prosperity. I agree that the application of the ‘Fiscal Rules’ will be damaging but I find it amusing that some of the ‘Letter Writing Economists’ were prominent in advocating such rules in the past as the way ahead for British Labour are now criticising those rules.

On March 19, 2024, the Shadow Chancellor appeared at the Bayes Business School (UCL) in London to deliver the – Rachel Reeves Mais Lecture 2024 – where she outlined how a new Labour government would reform the fiscal rules that the Tories had in place.

Her main complaint was that the rules led to “short-termism” and did not differentiate between recurrent and capital expenditure.

She said “Weak investment, with Britain alone among the G7 in having investment levels below 20 percent of GDP” was a major issue and undermined future productivity growth, which provided the capacity for non-inflationary real wages growth.

The “the new ‘British disease’ – in which short-term instability inhibits investment and drives up infrastructure costs, resulting in fewer, and smaller, new capital projects” had to be addressed.

She highlighted two issues (among others):

1. “austerity” – which had starved the economy of expenditure necessary to promote growth.

2. “failure to grasp a unique opportunity to undertake much-needed investment in our productive capacity. Investment was suffocated. Our supply-side weaknesses – in terms of both human and physical capital – were exacerbated.”

So a lack of growth in productive capacity driven by a lack of expenditure.

I have noted before that capital investment expenditure has a dual characteristic that makes it special among the aggregate expenditure categories.

On the one hand, it constitutes a flow of spending that adds to total spending in the current period and helps maintain employment.

But on the other hand, it adds to productive capacity, which then needs further expenditure growth to absorb it, if instability is not to arise.

Reeves then defined the fiscal rules that would “bind the next Labour government”:

1. “That the current budget must move into balance, so that day-to-day costs are met by revenues.”

2. “debt must be falling as a share of the economy by the fifth year of the forecast, creating the space to respond to future crises.”

In March 2016, the then Labour Opposition announced its so-called ‘fiscal credibility rule’ which Reeves has inherited.

Several of the economists who wrote to the Financial Times last week criticising Reeves were prominent in the design of the fiscal rules that the then Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell outlined in 2016 and took to the next general election.

The rule means that:

1. Recurrent expenditure must be matched at all times with tax revenue.

2. Capital expenditure would be matched with debt issuance.

3. But the overall debt to GDP ratio would fall over a five-year period.

The Tories cannot be blamed for these ‘rules’ even if they followed them themselves.

Labour itself advocated them with the help of some of the economists that are now complaining about them.

And regular readers will recall my long battles with those economists in the public sphere where I argued that the rules were untenable and would do exactly what the same economists are now claiming in their Financial Times letter.

Curious to say the least.

The overall fiscal framework invoked by Reeves is poorly conceived and not as some of those Letter-writing economists previously claimed were justified by economic theory.

They might have been justified by the mainstream macroeconomic theory but that body of work has categorically failed to stand up to the scrutiny of the real world.

Think GFC as an example.

But the Labour rules have no justification once we realise that the goal of fiscal policy is not to achieve some financial outcomes (debt to GDP ratio, primary balance, whatever).

Rather it is to underpin prosperity in a world where the private economy is inherently unstable.

In that sense, the rules work against prosperity, which is, in part, the basis of the claims made in the Financial Times letter, which I agree with.

Why investment leads to instability

While John Maynard Keynes did not consider economic growth in his essentially short-term model of output and employment, there were economists working in the so-called ‘Keynesian’ tradition that developed models of economic growth, which emphasised the importance of private saving and capital expenditure.

The famous work of – Roy Harrod (1939) and Evsey Domar (1946) produced what became known as the – Harrod–Domar model – of economic growth.

Of interest here was Harrod’s attempt to combine the short-run Keynesian expenditure multiplier with the concept of the investment accelerator (which linked the rate of growth in investment expenditure with the underlying GDP growth rate).

As background, please read the following blog posts:

1. Spending multipliers (December 28, 2009).

2. Investment and Profits (July 27, 2012).

On the one hand, investment expenditure generates current demand for goods and services, which stimulates flows of output and saving, and, along with the other expenditure categories, maintains employment.

On the other hand, Harrod considered investment expenditure to be largely driven by expectations of future movements in aggregate expenditure (GDP).

That is firms invest in capital equipment and productive capacity based upon what they think their sales at the time the capital equipment becomes productive would warrant.

In some industries, such investment involves long ‘gestation’ periods – that is a long time between making the decision to outlay the funds and the time when productive services start to flow from the augmented capacity.

This notion was the basis of the ‘investment accelerator’.

The question that interested Harrod related to the possible disjuncture between the expectations and the lived reality.

In other words, what would happen if the expectations of the firms turned out to be wrong?

Two broad errors could be made:

1. They invest too much and find they have excess capacity, which, then would lead to a significant reduction in investment in the period they realise their errors.

In that case, the cuts in investment expenditure trigger much larger declines in output (and saving) as firms lay off workers and those cuts reverberate via lost incomes throughout the economy.

This would trigger further cuts in investment expenditure (via a renewed accelerator effect) and the whole nasty show turns to a deep recession.

2. They invest too little and find they have insufficient capacity to meet the current expenditure for final goods and services – that is, final expenditure is outrunning the productive capacity (supply) side of the economy, which means the economy would be running up against the inflationary ceiling.

In that case, a sudden increase in investment expenditure (via the accelerator effect) could easily add to the inflationary pressure by stimulating further multiplier impacts before the new productive capacity had come on line.

The point of the analysis was that the dynamics of the capitalist system, which was intrinsically dependent on business firms expectations of an uncertain future, could easily become unstable – either prone to recessions or inflationary mania – as a result of expenditure mistakes being made which trigger the interaction between the demand-side (expenditure multiplier) and the supply-side (investment accelerator).

Another way of saying that is to recognise that investment expenditure adds to productive capacity which then needs to be ratified by at least that much extra expenditure for expectations to be realised.

Harrod defined a balanced growth path as being when firm expectations of aggregate demand are always correct.

Given the vagaries of the process, he considered that growth path to be an exception rather than the rule within a capitalist monetary economy.

Harrod considered the actual system to be always on a ‘knife edge’ – inherently unstable – and the possibility of veering into a deep recession with capital expenditure spiralling downwards or into an inflationary episode was high.

Later, in his 1947 paper, Evsey Domar focused on clarifying what he considered to be shortcomings in the analysis presented by John Maynard Keynes in his 1936 – General Theory.

(Reference: Domar, E.D. (1947) ‘Expansion and Employment’, American Economic Review, 37(1), March, 34-55).

Domar noted that the Classical belief in Say’s Law (supply creates its own demand and therefore unemployment is not possible for any extended period) had not only been refuted conceptually by Keynes, but subsequent historical experience had “badly shaken” the “comfortable belief”.

The ostensible reason is that:

A part of income generated by the productive process may not be returned to it; this part may be saved and hoarded.

So savings – the leakage from the flow of expenditure derived from produced income – means that demand can fall short of supply.

The “impression” that one gets from the General Theory is that in the absence of saving, full employment is guaranteed.

He thought that while that was easy to understand (“sounds perfectly straight and simple”), the derivation in the General Theory didn’t answer the questions:

… increasing productive capacity … must somehow be utilized if unemployment is to be avoided … Will a mere absence of hoarding assure such a utilization? Will not a continuous increase in expenditures (and possibly in the money supply) be necessary in order to achieve this goal?

His work tried to clarify that quandary and he introduced what he called the:

… the dual character of the investment process; that is, with the fact that investment not only generates income but also increases productive capacity.

He developed the link between the expansion of the demand-side (expenditure) and the supply-side (productive capacity) or in Harrod’s conception – the interrelationship between the expenditure multiplier and the investment accelerator.

The point was that capital expenditure (investment spending) impacted “both sides of the equation”:

… that is, it has a dual effect: on the left side it generates income via the multiplier effect; and on the right side it increases productive capacity … The explicit recognition of this dual character of investment could undoubtedly save much argument and confusion … it is difficult enough to keep investment at some reasonably high level year after year, but the requirement that it always be rising is not likely to be met for any considerable length of time … if investment and therefore income do not grow at the required rate, unused capacity develops. Capital and labor become idle. It may not be apparent why investment by increasing productive capacity creates unemployment of labor …

So demand must always be chasing the expansion in productive capacity and the link between the two – adequate growth in expenditure to absorb the growth in productive capacity can always be interrupted – leading to instability – usually a failure to achieve full employment.

For Harrod and Domar (as with Keynes) this inherent instability in the private economy was the primary justification for their advocacy of government intervention – to ensure that expenditure shortfalls would be filled with public spending to avoid damaging unemployment.

Domar recognised that inflationary periods were rare – “inflations have been so rare in our economy in peacetime, and why even in relatively prosperous periods a certain degree of underemployment has usually been present.”

These were the issues that economists debated at length in the Post World War 2 period up until the Monetarists took over the academy and defined them all away with their faux ‘free market’ concepts.

Back to the rules

While Reeves has allowed for an “escape clause” if the British Office of Budget Responsibility tells the government that the rules are untenable (for example, during a pandemic or deep recession), the problem is that by articulating the rule that overall debt must fall within five years, the Government then will craft investment expenditure plans accordingly.

And any understanding of the current reality – the debt situation and the expenditure shortfalls in public infrastructure after the devastating ‘starvation’ from the 14 years of Tory rule and the existential challenges (climate) – leads to the conclusion that even if the primary balance is zero on an ongoing basis (Rule 1), the Government would have to severely reduce public capital expenditure in real terms to go close to meeting the debt rule (Rule 2).

The only other way around it would be to:

1. Significantly cut recurrent expenditure, and/or

2. Increase tax revenue.

Which would create a primary surplus that they could offset against the capital budget (in an accounting sense) and reduce the call on debt-issuance (as an accounting not funding construct).

The arithmetic of all that doesn’t work out.

And by restricting capital investment, the Government will trigger the sorts of dynamics that Harrod and Domar well understood.

Reeves is banking on strong private sector expenditure growth driving GDP ahead of the expansion of public debt over the five years.

But by restricting public expenditure to somehow accord with her Rules, it is likely she will undermine private investment expenditure and then it is all over.

And with overall GDP growth in doubt, the ‘space’ for public investment (to meet Rule 2) will decline significantly.

It is a recipe for disaster.

There are many other problems with these rules which I have dealt with before:

1. What is recurrent and capital expenditure? Is expenditure on teachers not adding to future productive capacity?

2. The forecasts from OBR are notoriously poor – leaving the degree of precision in assessing performance against the Rules low.

3. What happens in year 5 when the debt ratio has still not fallen?

Conclusion

I thus agree with the Letter writers who note:

To follow through on these plans would be to repeat the mistakes of the past, where investment cuts made in the name of fiscal prudence have damaged the foundations of the economy and undermined the UK’s long-term fiscal sustainability.

Indeed.

oooooo

2) Bill Mitchell: EBZ eta pandemia

@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

ECB should take over and repay all the joint debt held by the European Commission after the pandemic https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62355

ECB should take over and repay all the joint debt held by the European Commission after the pandemic

February 13, 2025

There are repeating episodes in world macroeconomics that demonstrate the absurdity of the mainstream way of thinking. One, obviously is the recurring debt ceiling charade in the US, where over a period of months, the various parties make threats and pretend they will close the government down by failing to pass the bill. Others think up what they think are ingenious solutions (like the so-called trillion dollar coin), which just gives the stupidity oxygen. Another example is the European Union ‘budget’ deliberations which involve excruciating, drawn out negotiations, which are now in train in Europe. One of the controversial bargaining aspects as the Member States negotiate a new 7-year deal is the rather significant quantity of joint EU debt that was issued during the pandemic to help nations through the crisis. How that is repaid is causing grief and leading to rather ridiculous suggestions of further austerity cuts and more. My suggestion to cut through all this nonsense is that the ECB takes over the debt and insulates the Member States from repayment. After all, the debt wasn’t issued because the Member States were pursuing irresponsible and profligate fiscal strategies.

The debate in Europe is almost parallel to reality.

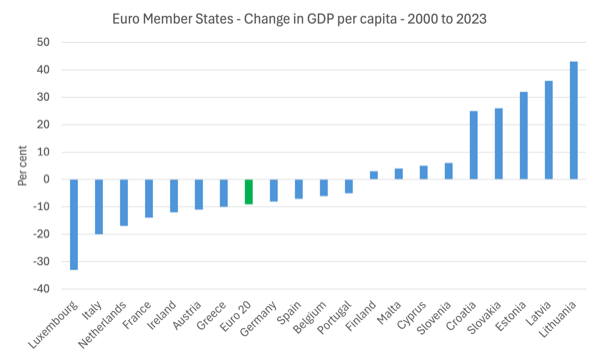

The following graph shows the percentage change in real GDP per capita in the Euro 20 Member States as well as the overall aggregate (in green) from 2000 to 2023 (latest data from Eurostat).

The majority of Member States are on average poorer in this respect, some significantly so.

The overall common currency area declined by 9 per cent over the period that the Euro has been in use (up to 2023).

When this data is available for 2024, the situation will have worsened a little, given the more recent national account figures.

I could assemble many indicators that would reinforce the conclusion that in economic terms, the adoption of the common currency has been disastrous for many nations, including the larger traditional EU Member States such as France and Germany.

The old Baltic satellites have fared better than those traditional EU states but they were coming off a very low base.

Second, remember Mario Draghi’s speech at CEPR on December 18, 2024 – Policy Insight 137: Europe: Back to Domestic Growth – where he did everything but admit that the architecture of the monetary union was dysfunctional.

He opened that address with this:

Productivity, incomes, consumption, and investment have been structurally weak in Europe since the turn of the millennium and have significantly diverged from the US.

It was not always this way. After the second world war, Europe’s labour productivity converged from 22% of the US level in 1945 to 95% in 1995. And for most of this period, domestic demand as share of GDP in the euro area stood in the middle of the range of advanced economies.

He then claimed that the technology shock (Internet) and the GFC meant that from the “mid-1990s onwards, relative growth in the US and euro area was pushed apart”.

He declined to mention a larger reality in the mid-1990s.

That the signatories to the Treaty of Maastricht had begun their so-called convergence process to ensure they could be included in Stage 3 of the Treaty introduction (the shift to the euro).

That convergence process saw these nations begin the austerity push which largely set in motion the stagnation that has followed.

Draghi tried to claim the GFC was somehow instrumental in creating a divergence between the US and the Euro area in terms of material prosperity:

… the great financial crisis and sovereign debt crisis, following which the orientation of the euro area shifted away from domestic demand.

This is true.

But why did the Euro area suffer a sovereign debt crisis and impose austerity when the US and other advanced countries avoided such turmoil?

The answer lies in the flawed monetary architecture that the neoliberals led by Jacques Delors foisted on the Member States which not only saw them surrender their currency sovereignty in favour of using a foreign currency (the euro) – the source of the sovereign debt crisis – but also coerced them into accepting fiscal rules that meant they did not have sufficient flexibility to defend domestic demand and economic activity against negative cyclical shocks.

And, moreover, the enforcement of the fiscal rules through the – Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) – by the technocrats in the European Commission, aided and abetted by the ECB and the IMF, meant that the capacity to produce income growth was decimated.

The GFC was as the name suggests ‘global’ in impact.

But it was the Europeans and other nations that insisted on imposing such austerity as the automatic stabilisers drove up deficits (as non-government spending declined and unemployment rose) increased.

The European economies signed up to that destructive response and have never really recovered since.

Draghi understands clearly the situation:

With investment stalling and fiscal policy becoming contractionary, both the corporate and government sectors shifted to being in surplus. As a result, domestic demand as a share of GDP in the euro area fell to bottom of the range of advanced economies …

The relative stance of fiscal policy was an important driver. From 2009 to 2019, the collective cyclically-adjusted fiscal stance in the euro area averaged 0.3%, compared with -3.9% in the US.

Bank loans also dried up in the Euro area between 2009 and 2016 because the demand for credit dried up.

The ECB claimed the lack of bank lending was because they didn’t have sufficient reserves and embarked on a QE program.

But it was never about a lack of reserves and all about lack of confidence.

Draghi also had a veiled shot at Germany in his speech:

Moreover, European policies tolerated low wage growth as a means to increase external competitiveness, compounding the weak income-consumption cycle. Since 2008, annual average real wage growth has been almost four times higher in the US than the euro area.

The leader in the ‘low-wage charge’ was Germany, who via the Hartz attacks on labour market conditions, thought they were being clever by gaming the other Member States and ensuring their export sector would boom.

Please read my recent blog post – Germany’s sectoral decline and its obsession with fiscal austerity (February 3, 2025) – for more discussion on where that strategy has landed Germany.

Draghi recognised that the policy model deployed within Europe that suppressed domestic demand via fiscal austerity and low-wages and sought growth via export markets (particularly China) is “no longer appears sustainable”:

For some time now, the Chinese market has been become less favourable for European producers as growth slows and local operators become more competitive and move up the value chain. Exports to China have stagnated since 2020.

The problem is that the ideological mindset of the European polity and the macroeconomic policies that they envisage are not:

… well placed to fill the gap left by external demand.

That summary really amounts to a devastating critique of the whole structure of the monetary union, of which Draghi was a central figure in enforcing.

Of relevance to the next part of this discussion is the fact that Draghi realises that:

If the EU were to issue debt jointly, it could create additional fiscal space that could be used to limit periods of below-potential growth …

If EU bonds traded like equivalent safe assets today, the convenience yield would push borrowing costs below growth rates.

This differential would allow the EU to issue additional debt – potentially up to 15% of GDP – and roll it over indefinitely without requiring payments from the Member States.

In other words, Europe should abandon the notion that the major counter-cyclical macroeconomic policy capacity should remain at the Member State level, which are constrained by the fact that their debt is subject to credit risk (because they are issuing debt in a currency foreign to them) and the fiscal rule monitors are watching them like hawks ready to shunt them into the EDP and force austerity cuts on their governments.

In my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – I argued that the way out for Europe was to create a true federation which a federal fiscal capacity that would dominate the Member State policy capacity in financial terms.

That option was deliberately eschewed by the founders because they knew Germany, for one, would never sign up to it and they also desired to limit the capacity of national governments – they were neoliberals after all.

The concept of EU joint debt or debt issued by the European Commission rather than the Member States is now dominating the current discussions about the next EU ‘budget’.

Politico carried a story earlier this week (February 11, 2025) – The EU’s ticking debt bomb — and why it matters for its next budget – which captures the European mentality in the headline.

“Ticking debt bomb”.

A friend sent me the link with the E-mail heading ‘Ticking’.

I laughed.

The EU Member States are embarking on the torturous process of designing the next 7-year fiscal policy (budget) with a rather substantial pandemic hangover in the form of the joint debt that has to be repaid from 2028 (the budget period runs from 2028 to 2034).

Nothing is quick in the EU.

Politico notes that:

Deliberations are even more difficult this time around because the Commission’s €300 billion joint debt program to rescue the EU economy after the Covid pandemic is up for repayment from 2028. Without a new plan, that could take a huge chunk — between 15 percent and 20 percent, according to the Commission’s estimates — out of the bloc’s spending power.

So designing a “repayment plan before 2028” is occupying the technocrats and politicians.

The four most exposed nations face significant ‘worst-case’ contribution scenarios – Germany (€35.8 billion), France (€28.6 billion), Italy (€19.6 billion), and Spain (€13.4 billion).

All these economies are in decline and some might say structurally so.

The first Commissions strategy was to use “levies on carbon emissions, imports and profits of multinationals” to repay the debt but that was rejected by the Member States because it would have diverted a vital source of revenue for themselves.

The reality is that:

The default option consists of national governments filling the hole by sending more money to Brussels.

But that is highly problematic given the fiscal rules and the lack of solidarity within the so-called Union.

Politico notes that:

Countries from Northern Europe — which have received a relatively small share of the EU’s post-Covid aid — are loath to pay more into the budget …

Which goes to the heart of the problem of the architecture.

The on-going hostility of the rich Northern Member States to making unconditional transfers within the Union to help other Member States deal with asymmetric shocks and poor economic performance is why the monetary union should never have been created in the first place.

Member States within functional federations (say Australia) know that the federal fiscal capacity has to be able to make asymmetric fiscal transfers when the need arises.

Just this morning, the Australian government announced a large fiscal package that will help Northern Queensland deal with the recent major flooding episode that has devastated regions and town in that part of the nation.

No-one in the Southern States blinks and demands payment in return.

But the Northern European states are arguing they want cuts to assistance to other states within the Union if they are forced to contribute to paying off the Covid debt.

They clearly do not see a ‘federal’ system and are suspicious of the Southern Member States.

Which is one of the reasons the dysfunctional architecture was installed in the first place – Germany publicly stated its mistrust of Italian officials, for example.

In fact, during the late 1990s convergence process, German officials argued that Italy should be excluded from Stage 3 because its public debt to GDP ratio was too high (outside the SGP parameters).

It was only when it was pointed out that Belgium, was in a similar situation, that the Germans realised that tack wouldn’t work.

Politico reports that:

But Germany and its fiscally conservative allies see this as a slippery slope toward a fiscal union, in which the Commission permanently takes on the debts of its 27 members.

And Germany will never allow that to happen.

Here is my suggestion with the current design parameters of the system (noting I advocate abandoning the whole common currency):

1. The responsibility for the joint debt be taken off the European Commission and handed over to the ECB. That could easily be done.

2. The ECB then pays the debt off when payments fall due with a stroke of a computer keyboard. It is the currency issuer and has infinity minus one euro penny capacity to do this.

3. No liability or conditionality would be imposed on the Member States.

No fiscal crisis.

No austerity necessary when the opposite (as Draghi notes) is required.

QED.

Critics would claim this approach would just fuel so-called moral hazard and encourage the Member States to spend up big and issue stacks of debt.

First, they cannot under the fiscal rules ‘spend up big’.

Second, the bond market yields would rise before they could issue ‘stacks of debt’.

Third, and more importantly, the joint debt that is causing all the controversy and heartache was not issued as a result of fiscal profligacy by the Member States.

Nations around the world were facing a pandemic, which we had no real understanding of and no certainty of what was going to happen.

Governments had to act in a significant manner to provide some surety to their citizens in such an uncertain period.

So the European officials could easily make the case that this joint debt was something quite different (which it was) relative to national government debt issued to cover fiscal deficits that are, in part, the product of discretionary fiscal decisions they have taken (good or bad, prudent or irresponsible).

Conclusion

Such an immediate and simple solution is too obvious for the tortured souls in the European Commission.

oooooo

Geure herriari, Euskal Herriari dagokionez, hona hemen gure apustu bakarra:

We Basques do need a real Basque independent State in the Western Pyrenees, just a democratic lay or secular state, with all the formal characteristics of any independent State: Central Bank, Treasury, proper currency, out of the European Distopia and faraway from NAT0, maybe being a BRICS partner…

Ikus Euskal Herriaren independentzia eta Mikel Torka

oooooo