@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

The decline of economics education at our universities https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62349

The decline of economics education at our universities

February 6, 2025

Economics courses at university in Australia have been under threat for several decades now and many specialist degrees have been abandoned by universities as student enrolments declined. When the federal government merged the vocational higher education institutions (Colleges of Advanced Education) with the universities in the late 1980s, traditional economics faculties were swamped with half-baked ‘business’ courses in management, HRM, marketing and whatever which then attracted the aspiring ‘entrepreneurs’ who were told by the marketing literature that they would be fast-tracking into management careers in the corporate sector. The reality was that these programs did not equip the students to do very much at all (perhaps erect marketing displays in supermarkets!) but the impact on economics programs was devastating. The most recent Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Bulletin published on January 30, 2025 contained an article which bears on this issue – Where Have All the Economics Students Gone?. I discuss some of the implications of the decline in student numbers in economics and the lack of diversity that existing programs have for societal well-being.

A short history

In 1994, I was elected by my colleagues to be the next Head of Department of Economics at the University of Newcastle.

It was still a time when ‘democracy’ ruled in Australian university departments and I was actually the last elected head at that university.

The tides of neoliberalism and corporatisation were already beginning and during my term, consultants recommended that the university cease elections for all the senior positions (HOD, Deans, President of Senate, etc) and instead move to appointments only.

Obviously, this reduced the voice that we had as the appointments were crafted to maintain control of the new KPI-driven agenda.

I remember that after my first term (4 years), I was invited to continue for a second term by the Vice Chancellor.

At the meeting, he said ‘welcome, you are one of us now’!

I asked him who ‘us’ were and he replied part of line management.

I demurred and told him that he was wrong and that I was just the representative of the collective (my colleagues) to management and that he should not think otherwise.

I recall him being a bit surprised (-:

But those days were the beginning of a long decline for economics education in the university system.

Up to that time (1994), the federal government had allocated funding to States to fund capital and recurrent expenditure in universities on a triennial basis.

The public universities in Australia are legislative creations of the states but it is the federal government money that kept them afloat.

The triennial funding system gave universities some security and continuity and departments were able to make pitches on the basis of the so-called ‘establishment’ (which carried a number of appointments).

The link between student load and the establishment was hazy and the latter was driven more by the political skills of the university admin and then within each institutions by the skills of the faculty bosses (Deans and HODs).

When I became HOD, the Economics Department was the largest (in staffing) in the university and the staff had enjoyed a lot of security for some years.

Things changed dramatically around that time though.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the federal government created a unified tertiary system – merging the universities, institutes of technology and colleges of advanced education.

It was brutal shift and caused massive disruption to the internal structures of the universities.

Overnight, we had university academics with PhDs who had built research careers forced to work with CAE staff who were really school teachers – no advanced degrees, no research background and used to long holidays over Summer (which is the time the active researchers write up their competitive research grant applications).

The mergers created ‘business schools’ and downgraded the position of economics – which was seen as a service course for these new ‘business degrees’, rather than the core academic discipline of the traditional faculties.

I recall getting memos from senior managers demanding to know why the first year failure rates, which were always around 30 per cent, were not like the near 100 percent pass rates in management.

The emphasis was on why we were bad rather than why the 100 per cent pass rates were bad and avoided the fact that students in management were given easy exams which almost anyone could pass with little understanding of anything.

But things became much worse soon after.

The federal government, as part of its unified tertiary system, abandoned the triennial funding arrangement and instead introduced the ‘relative funding’ model, which provided a single operating grant to institutions based on student load.

Extra funding was provided – so-called ‘research quantum’ – on the basis of research output.

Within institutions, the relative funding model provided $s to disciplines based on enrolments which meant that the old concept of an establishment profile was abandoned and the cold winds of ‘load’ became the source of funds and staffing.

There were many distortions in teaching and research that followed – short-termism, load rather than quality, etc – which I won’t go into here in any detail.

But the rush was then on to pack the rafters with students.

Also the ‘export market’ opened up and overseas students were seen as the way to ease funding shortfalls.

Further quality distortions accompanied that ‘gold rush’ which persist to now.

But in my first meeting with the Dean after taking on the HOD role I was told that the new relative funding model meant our Department budget had to lose about $A2 million in what was only a $4.5 million total annual allocation.

The reason – student load had diminished as the ‘business degrees’ entered the fray and economics was not seen as a desirable course of study.

In my time as HOD, the Department shrunk from around 32 full-time staff to around 14 – approximately (I have no formal records to be exact) through various attrition programs pursued by the Dean.

After my second term, the new managers of the Faculty forced a closure of the Department altogether and the abandonment of the Economics degree.

At that time, I negotiated with the Vice Chancellor to leave the Faculty structure and to shift my research group – Centre of Full Employment and Equity – as a stand-alone entity within the University structure and only report to the DVC Research.

I was able to do that because I was attracting a significant amount of external research funding which meant I could fund my group without faculty support.

It was very liberating but the plight of the economists within the faculty just deteriorated further because the majority of the research income generated by ‘economists’ went with me to CofFEE.

Anyway, the point of all that is that the decline in student interest in economics had had huge impacts across Australian universities.

RBA research

The RBA article (cited in the Introduction) notes that:

The size and diversity of the economics student population has declined sharply since the early 1990s, raising concerns about economic literacy in society and the long-term health of the economics discipline.

The RBA notes that economics was “one of the most popular subjects in high school three decades ago”.

But that has changed dramatically since the 1990s.

UAC is the Universities Admissions Centre and the RBA research examines data for just NSW and the ACT.

However, the trends they detect are national.

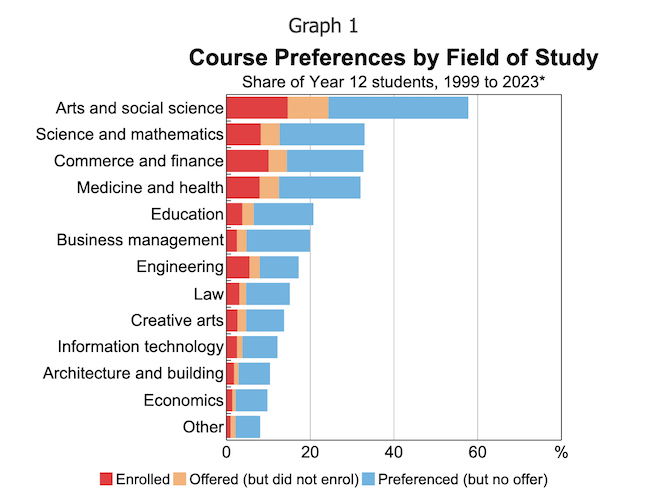

The following graph (Graph 1 in the RBA report) shows that “Between 1999 and 2023, only around 10 per cent of all Year 12 students included an economics course among their preferences to UAC, with just 1 per cent of all students actually enrolling in one”.

The decline since has not just been in overall numbers.

The RBA also finds that:

… there is a growing uniformity among economics students, and this also extends to those who become economists or apply economics in their careers

What do they mean?

Female students who studied Year 12 economics were less likely to include an economics course in their preferences than their male counterparts over the 1999–2023 period. Instead, female high school economics students were more likely to show interest in arts and social science, medicine and health, and law than their male peers.

Interestingly, of the females who initially express a preference with the UAC process for economics but “who ultimately chose not to enrol in an economics course had, on average, higher ATARs than males who enrolled in economics”.

The ATAR is the Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank – a score used by the admission centres to allocate students across university courses.

That means the academically brighter female students did not go into the economics programs, which are dominated by lower scoring males.

The other diversity angle is the students’ socio-economic background.

The RBA finds that:

… students who are interested in economics at university tend to belong to advantaged socio-economic groups, including students from non-government schools …

So the economics students are from the rich families and have attended the very expensive private secondary schools – which means they will have accumulated certain values about their ‘position’ in society.

I discussed elements of that tendency in these blog posts among others:

1. The conflicting role played by education in social mobility and class reinforcement (August 9, 2023).

2. The evidence from the sociologists against economic thinking is compelling (November 12, 2019).

3. The brainwashing of economics graduate students (February 12, 2019).

4. Economics curriculum is needed to work against selfishness and for altruism (September 19, 2018).

5. Education – a vehicle for class division (November 23, 2010).

A large body of research in social sciences (around the world) has demonstrated that standard economics programs at our universities breed people with sociopathological tendencies who elevate greed above empathy.

There is clearly some self-selection bias because the studies have never really isolated the impacts of the teaching programs from the tendencies of the students going into the programs.

One 2005 study that was published in the journal Human Relations – Personal Value Priorities of Economists – found that:

1. Economics students exhibited less altruism and more self-interest in their “first week of their freshman year”.

2. That is, “differences between students of economics and students from other disciplines were already apparent before students were exposed to training in economics”.

3. After one year of study these differences were maintained and stable.

4. By the final year of study, the emphasis on “achievement, power, hedonism” were sustained and economic students valuation of “benevolence”, which we might think of as being empathy towards others, had declined significantly.

In their 1993 article – Does Studying Economics Inhibit Cooperation? – economist Robert Frank and psychologists Thomas Gilovich and Dennis Regan summarised the extant literature and conducted a series of their own experiments to explore whether there are significant differences between “economists and noneconomists” in relation to whether they exhibit sociopathological tendencies.

They conclude that:

1. “that economists are more likely than others to free-ride”.

2. “economics training may inhibit cooperation …”

3. And, interestingly, that “the ultimate victims of noncooperative behavior may be the very people who practice it”.

4. And students in economics classes are more likely to lie when confronted with experiments about generosity – that is, claiming to be more generous than they were.

Further, an LSE Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper (No. 1938, July 2023) – Are the upwardly mobile more left-wing? – found that:

1. “that higher own status and higher-status parents independently produce Conservative voters.”

2. Higher own status leads to “opposition to redistribution”.

3. “individuals with the most Right-wing attitudes (and votes) are then those with high social status whose parents were also of high social status.”

The problem then is that not only are the number of economists emerging from universities declining but there is also a growing concentration among males from privileged backgrounds that are liable to exhibit the sorts of tendencies noted above.

Think about that in the context of designing progressive government policy.

It is not an attractive future.

I noted above that the decline was, in part, driven by the introduction of ‘business’ into the traditional economics faculties.

I didn’t want to give the impression, however, that this was the full story.

A not insignificant part of the decline can be traced to the way we taught economics in the 1970s and 1980s, which create sterile learning environments for students.

When I was an economics student, macroeconomics, for example, was taught from a critical perspective.

The textbooks we used contrasted the range of views of the various schools of thought and left it to the students to work out what they thought about the various conflicts that arose.

It was a more general education which emphasised reading and thinking about the classical literature in the subject.

We were ‘well read’ in the parlance and were required to study history, different economic systems (comparative systems), philosophy of science, logic, methodology, and more.

The subject matter was also integrated with knowledge from the other social sciences – which meant that we were exposed to literature in sociology and psychology for example.

That tempered the way we thought about policy and society.

In the 1980s that approach changed rather dramatically.

The new way of teaching out of the US created textbooks that provided students with ‘the one model’ and little critical analysis.

Universities started dropping the history of thought courses and the other approaches that had enriched the previous generation of students.

So there was little debate permitted – this is the model – learn it and that was it.

That model – the New Keynesian approach – defied reality and has spawned the terrible policies that I rail against regularly in my own work.

The depiction of the capacity of currency-issuing governments as just large households with similar financial constraints became central to the pedagogy and is, of course, plain wrong.

Remember the August 2008 article by Olivier Blanchard – The State of Macro – where he noted that mainstream economics at the graduate level has evolved to become an exercise in following:

… strict, haiku-like, rules … [the economics papers] … look very similar to each other in structure, and very different from the way they did thirty years ago …

Graduate students are trained to follow these ‘haiku-like’ rules, that govern an economics paper’s chance of publication success.

So if an article submission does not conform to this haiku-like structure it has a significantly diminished chance of publication.

So we get a formulaic approach to publications in macroeconomics that goes something like this:

- Assert without foundation – so-called micro-foundations – rationality, maximisation, RATEX.

- Cannot deal with real world people so deal with one infinitely-lived agent!

- Assert efficient, competitive markets as optimality benchmark.

- Write some trivial mathematical equations and solve.

- Policy shock ‘solution’ to ‘prove’, for example, that fiscal policy ineffective (Ricardian equivalence) and austerity is good. Perhaps allow some short-run stimulus effect.

- Get some data – realise poor fit – add some ad hoc lags (price stickiness etc) to improve ‘fit’ but end up with identical long-term results.

- Maintain pretense that micro-foundations are intact – after all it is the only claim to intellectual authority.

- Publish articles that reinforce starting assumptions.

- Knowledge quotient – ZERO – GIGO.

This routinisation creates publication bias and policy advice that has little bearing on reality.

And it is boring, which is why fewer students want to pursue these programs.

And the ones that do are prone to the tendencies I discussed above.

Teaching fictions is not going to be attractive to students who want to be exposed to critical perspectives that relate to the real world.

Economists are to blame for the decline in student numbers because they have engaged in such restrictive Groupthink.

Conclusion

Economics education as it is practised in our learning institutions is largely propaganda.

Students see through that and eschew it.

And the ones that don’t become the policy makers and the world deteriorates further.

oooooo

Economics as politics and philosophy rather than some independent science https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62352

Economics as politics and philosophy rather than some independent science

February 10, 2025

Last week, I wrote about – The decline of economics education at our universities (February 6, 2025). This decline has coincided and been driven by an attempt by economists to separate the discipline from its roots as part of the political debate, which includes philosophical views about humanity and nature. In her 1962 book – Economic Philosophy – Joan Robinson wrote that economics “would never have been developed except in the hope of throwing light upon questions of policy. But policy means nothing unless there is an authority to carry it out, and authorities are national” (p.117). Which places government and its capacities at the centre of the venture. Trying to sterilise the ideology and politics from the discipline, which is effectively what the New Keynesian era has tried to do, fails. The most obvious failure has been the promotion of the myth of central bank independence. A recent article in the UK Guardian (February 9, 2025) – You may not like Trump, but his power grab for the economic levers is right. Liberals, take note – is interesting because it represents a break in the tradition of economics journalism that has been sucked into the ‘independence’ myth by the economics profession.

I have written extensively about this topic in past blog posts, including among others:

1. The central bank independence myth continues (March 2, 2020).

2. ECB continues to play a political role making a mockery of its ‘independence’ (June 12, 2018).

3. Censorship, the central bank independence ruse and Groupthink (February 19, 2018).

4. The sham of ECB independence (October 24, 2017).

5. Trump might do us a favour – expose the myth of central bank independence (November 14, 2016).

6. The sham of central bank independence (December 23, 2014).

7. Central bank independence – another faux agenda (May 26, 2010).

The UK Guardian article cited in the Introduction notes that “monetary policy is political. The question is how to make it democratic”.

I am not endorsing the contents of the article except that it is correct in bringing to our attention that there is tremendous scope available for progressive policies if we give up on the idea that monetary policy is somewhere separate from politics and ideology.

The idea that politicians should not be involved and responsible for the major macroeconomics policy settings is ludicrous and testament to the success the neoliberals have had in coopting government to serve the interests of a few at the expense of the many.

In our 2017 book – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, September 2017) – we discussed the concept of depoliticisation as a characteristic of the neoliberal era where the state was reconfigured to serve the interests of capital rather than society in general.

Depoliticisation was justified in the words of the UK Guardian article by claims that “politicians, who only care about getting elected, aren’t the right custodians of monetary policy, since what looks like good policy in the short term (such as lowering rates in advance of an election) can become bad policy in the long term.”

In graduate school, this claim is cloaked in all sorts of technical, mathematical mumbo-jumbo (for example, Dynamic inconsistency), but the motive is clear enough.

That is, the motive was to make it easy for politicians to avoid responsibility for harsh policy settings that favour the wealthy and give our elected representatives cover for running fiscal policy that is biased towards austerity – “Oh, if we don’t cut the deficit, then the independent central bank will hike interest rates because they fear increased inflation, and that would be bad, wouldn’t it”.

Game over.

No questions asked.

In relation to monetary policy, the Guardian article also notes that “this field is undoubtedly too technical for politicians to understand. It should be left to the experts”.

The ‘too technical’ argument has been a common ruse.

As an aside, and relevant to my post last Thursday – The decline of economics education at our universities (February 6, 2025) – when the KPI-touting managers wanted to take over the universities in Australia and exclude academics from the key legislative positions within the institutions the same logic was used.

I recall a meeting where a DVC said to me – that the sector had become too complex for academics to understand fully and thus governing decision-making with the university had to be ceded to full-time managers, rather than elected academics serving their colleagues.

It was a laughable ruse.

The Guardian article also sees through that claim – “the same is true of the “technical” nature of monetary policy. Do we really think it is that much more technical than tax policy, defence policy or environmental policy?”

The article concludes that “a fear of democracy itself” that is behind the depoliticisation of monetary policy (although the writer doesn’t use that terminology).

I am often confronted with questions during presentations that we have to shackle the politicians because they cannot be trusted.

So the alternative is to ditch democratic accountability in favour of ‘technicians’ which then creates monsters like the IMF, the European Commission, central banks etc.

And economists in this tradition then create a fictional world – with all sorts of published papers purporting to show why any departure from that fiction would be disastrous.

Fiction about fiction.

And we believe it.

In the Buddhist script – Caṅkī Sutta (MN 95) – we read:

Suppose there were a row of blind men, each holding on to the one in front of him: the first one doesn’t see, the middle one doesn’t see, the last one doesn’t see. In the same way, the statement of the Brahmans turns out to be a row of blind men, as it were: the first one doesn’t see, the middle one doesn’t see, the last one doesn’t see.

Except the person at the front of the row is the economist and they deliberately create the ‘blindness’

Remember the interview that famous US macroeconomist Paul Samuelson gave to Mark Blaug in 1988 film – John Maynard Keynes – Life – ideas – Legacy – when he said:

I think there is an element of truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times … Once it is debunked takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have … anarchistic chaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that long-run civilised life requires.

So economists know they are lying to the public about fiscal matters because if the truth about the capacity of government and the reality of all the charades about debt issuance, central bank independence, and the rest of it was [were] understood, then we would make greater demands on government.

Just like religion that attempts to control us through fear of a terrible afterlife, economics as practised by the mainstream is a control mechanism to ensure the powerful retain their position in the pecking order and their wealth and privilege.

Remember the comment made by Keynes in the General Theory Chapter 12. The State of Long-Term Expectation (p.157):

There is no clear evidence from experience that the investment policy which is socially advantageous coincides with that which is most profitable.

Which Joan Robinson reminded us in her 1962 book that Keynes “was considering the bias of private enterprise in favour of quick profits”.

Economics as a discipline has morphed into becoming a support mechanism to ensure private profit continues to be accumulated by the few while the rest of us increasingly struggle with various challenges that such a bias has created – deterioration in the quality and availability of housing, environmental degradation, diminishing employment quality, diminishing quality and availability of health care, increased corporatisation of education, etc

And the conduct of central banks in this era is one significant aspect of this bias.

Under the pretense of ‘fighting inflation’, they manipulate interest rates to the benefit of private bank shareholders, financial wealth holders and oversee the massive redistribution of income away from low-income mortgage holders towards high-wealth asset owners.

They demand that unemployment has to rise to reach the unobservable NAIRU, which evades accurate statistical estimation – which is so inexact that the concept is devoid of practical use as a policy guide, quite apart from its vacuous theoretical status.

They then threaten governments with even more punishing interest rate hikes, if they don’t cut fiscal outlay to ensure the unemployment rises, and, meanwhile, they regularly make political statements about the dangers of deficits etc, then tell everyone that they are independent of the political process.

In – Chapter 24. Concluding Notes on the Social Philosophy towards which the General Theory might Lead – Keynes mused (and longed for) a time when the rate of interest dropped to very low levels and the rate of profit on capital would reflect “little more than their exhaustion by wastage and obsolescence together with some margin to cover risk and the exercise of skill and judgment” (p. 375).

This was his famous comment about “the euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital” (p.376).

In Australia, the shift towards depoliticisation accelerated in the 1980s (under a Labor government to boot).

Major institutional changes were foisted on us by the government of the day in terms of the way the central bank operated to support fiscal policy interventions.

Prior to 1982, the federal treasury (coordinating the central bank, the RBA) ran what was called a ‘tap system’ in relation to government debt.

The system saw the government determine how much debt it wanted to issue.

Then the government would set the interest rate (yield) and supply the bonds to investors at that rate according to the demand received.

Sometimes investors did not take up as much as the Government desired to sell because they thought the fixed yield was too low.

The government would then instruct their accounts to create contra entries in the RBA-Treasury accounts so that the shortfall was closed by the RBA sending dollars to the government and receiving bond assets in return.

It was unambiguously a case of the government borrowing from itself, which exposed the whole fallacy of the government deficits requiring non-government sector debt funding.

And as the neoliberal era intensified, such leaks in the ‘story’ (the fiction) could not be tolerated.

The tap system was relentlessly attacked in the early 1980s by the conservative government, economists, and the financial community as they all developed their neo-liberal credentials.

What transpired was the development of – The Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) – which in its own words “is a specialised agency within the Treasury portfolio responsible for management of Australian Government debt.”

So Treasury moved a few desks around and then pretended that the debt-issuance infrastructure was now at arm’s length from the government.

The AOFM’s activities include the issue of Treasury Bonds, Treasury Notes, management of the Australian Government’s cash balance, and management of a portfolio of debt and investments.”

The creation of the AOFM was largely cosmetic – it is still unambiguously part of the consolidated government as is the RBA.

The AOFM claimed that “The TAP mechanism was not sustainable with increasingly flexible interest rates” (Source) but that statement is conditional on the related assertion that the RBA should not directly engage in those contra accounting entries – that is, directly purchase government debt.

The condition was left unchallenged by the AOFM because they are ideological warriors and by the time it was created Milton Friedman was all the rage and economists all believed that if the central bank made such entries then inflation would accelerate.

Another myth that lead to institutional changes that reinforced the power hegemony of the wealthy.

To get an idea of the historical debate you might want read this speech, which was the text of a presentation made by Peter McCray, Deputy Chief Executive Officer, AOFM in 2000 (the text is no longer available on line – I saved it in my archives).

In terms of the fact that the tap system sometimes led to the government lending to itself, McCray says that this would be

… breaching what is today regarded as a central tenet of government financing – that the government fully fund itself in the market. It then became the central bank’s task to operate in the market to offset the obvious inflationary consequences of this form of financing, muddying the waters between monetary policy and debt management operations.

First, this so-called central tenet is just one of the bits of ideological baggage that have constrained governments from creating full employment.

There is no foundation in economic theory for it.

It is a political statement.

Second, the statement “obvious inflationary consequences” is also not based on any monetary theory nor is it evidence-based.

Once again it is a political statement reflective of the free market ideology.

It is not obvious when you have persistently high unemployment that net government spending not accompanied by reserve drains (bond issues) will be inflationary.

It is highly likely that it will not be!

But at any rate it is an empirical question.

Statements like that from the senior AOFM official just showed how captive this part of the public service became under the neo-liberal fist!

The neo-liberal era demanded that tried and tested social democratic practices give way to privatisation, outsourcing and a primacy of the capitalist market place in allocating resources.

It demanded a diminution in the role of government in terms of promoting general welfare advancement in favour of becoming an agent of capital to benefit the few.

We are now living through the costly aftermath of following that route.

In August 1982, the tap system was replaced with an ‘auction model’ mainly because of the alleged possibility of a funding shortfall.

A totally spurious concept of-course.

To construct the shortfall as a problem was a purely neo-liberal contrivance.

They claimed it introduced uncertainty to the funding process.

It did not in actual fact do anything like that.

What it meant was that investors had converted a desired amount of their wealth holdings into government bonds and were happy with their portfolios at the rate of return on the paper that the government was offering.

That is all it meant.

The auction model merely supplied the required volume of government paper at whatever price was bid in the market.

So there was never any shortfall of bids because obviously the auction would drive the price (returns) up so that the desired holdings of bonds by the private sector increased accordingly.

At that point the secondary bond market started to boom because institutions now saw they could create derivatives from these risk-free assets etc.

The slippery slope was beginning to be built as the casino expanded.

It was also claimed by the AOFM that (Source):

The adoption of tenders for debt issuance was critical in freeing up the key risk-free market yield in the economy. This proved essential for the financial innovation that was to occur in the financial markets in the following years.

But what that meant was that the financial market gamblers just wanted the security of a risk-free asset upon which it could use as a benchmark to price its other riskier bets.

And they wanted the yields to be as high as possible to enhance the returns across the board.

And if they were in control of setting those bond yields (as the auction system allowed) then times were sweet.

It was corporate welfare at its best at a time when the corporate sector was leading the charge against welfare for people – claiming it undermined work incentives etc.

The other major reason for introducing the auction method is well expressed in the following tract from McCray’s speech.

He is talking about the so-called captive arrangements, where financial institutions were required under prudential regulations to hold certain proportions of their reserves in the form of government bonds as a liquidity haven.

… the arrangements also ensured a continued demand from growing financial institutions for government securities and doubtless assisted the authorities to issue government bonds at lower interest rates than would otherwise have been the case … Because such arrangements provide governments with the scope to raise funds comparatively cheaply, an important fiscal discipline is removed and governments may be encouraged to be less careful in their spending decisions.

So you see the ideological slant.

The pressure to change the system was thus not only about corporate welfare but also about the conservative desire to force voluntary limits on what the Federal government could do in terms of fiscal policy.

This was the period in which full employment was abandoned and the national government started to divest itself of its responsibilities to regulate and stimulate economic activity.

The legacy is the mess we are in now.

The real reason for the shift to the auction model administered by the AOFM was provided by McCray in his speech to the ADB:

The reduced fiscal discipline associated with a government having a capacity to raise cheap funds from the central bank, the likely inflationary consequences of this form of ‘official sector’ funding … It is with good reason that it is now widely accepted that sound financial management requires that the two activities are kept separate.

Read it over: reduced fiscal discipline … that was the driving force.

They proponents of the auction system wanted to wind back the government’s role of promoting societal well-being and restrict its ambit to assisting capital.

The plan was to force as many voluntary constraints on the operations of government that they could think of and then get economists to write papers justifying the constraints.

All these institutional shifts were basically unnecessary (because there is no financing requirement), many were largely cosmetic (the creation of the AOFM) and all were easily able to be sold to us suckers by neo-liberal spin doctors as reflecting … “sound financial management”.

We were all marching in the row of the blind.

Conclusion

What this allowed was the relentless campaign by conservatives, still being fought, against the legitimate and responsible use of fiscal deficits.

It also led to the abandonment of full employment.

And the legitimate role of government was reduced before our very eyes and we now allow unelected and unaccountable central bank policy makers to impose huge costs on the most disadvantaged workers in our communities under the guise of TINA.

The reality is that modern monetary economies do not even need central banks.